I’m Not Like a Regular Mom, I’m a Pool Mom

An Ode to Community Recreation and the End of Summer

Last weekend, I washed our pool towels for the first time in months. Over the course of the summer, the terrycloth has grown stiff from chlorine, Elsa and shark faces faded from many days drying drooped under the sun. For weeks, those towels have been flung over plastic backyard chairs quickly, next to drippy bathing suits, on the way to draw a warm bath for two blue-lipped, tired kids.

This week, we are trading in our bathing suits and pool gear for untenable schedules and new backpacks. Everyone in our house is a little excited for a new season. Everyone is also in mourning. The end of summer is always a little heartbreaking.

Over the summer months, on Monday-Friday mornings, I tried to pull together some semblance of productivity—to push words around on my screen or organize fall teaching. Most often though, I just stared at my computer and rubbed my face, wondering what to do next, counting how many days were left of summer, and checking the clock, knowing soon it would be decision time: Open swim at the community pool began, on weekdays, at 1pm, and I would have to decide whether to give up on the day or push through.

In June, after breaking for lunch, I often returned to the room where I work, going through my performance of productivity for a few more hours. My husband is a high school teacher who gets summers off, so for two months, I don’t have to perform the role of primary caregiver. I saddle him with as much as possible while I still can, including swim lessons and play time at the pool.

But by August, I was tired of being indoors. I began forcing myself to put my work down, knowing that as I pulled on my one-piece bathing suit, my kids would holler, excited that I was joining them, choosing to be fun, and I would feel important again, valued in a way I did not feel when I stayed home alone.

On the five-minute drive to the pool, I felt sure I’d be plagued all afternoon by whatever I had left undone, but once I schlepped the bags of food and gear past the pool check-in counter, sat down in the poorly shaded grassy area, smelled the pool chemicals, and watched my kids don their goofy goggles, I stopped thinking about whatever troubled me. Everything urgent and suffocating mattered less, looked inconsequential. I was happy.

When I was young, each summer I spent hours by pools, suntanning with friends. In elementary school, for a few years my mother rented a town home in Burbank that had a shared pool, enclosed by an iron gate for which we needed a special key. I spent every sunny day I could practicing dives and dunks and getting what my children and I now call “pool toes”—raw blisters on the pads of my feet, from so many hours pushing off rough concrete walls into the water, where I spun and twisted my body into new shapes.

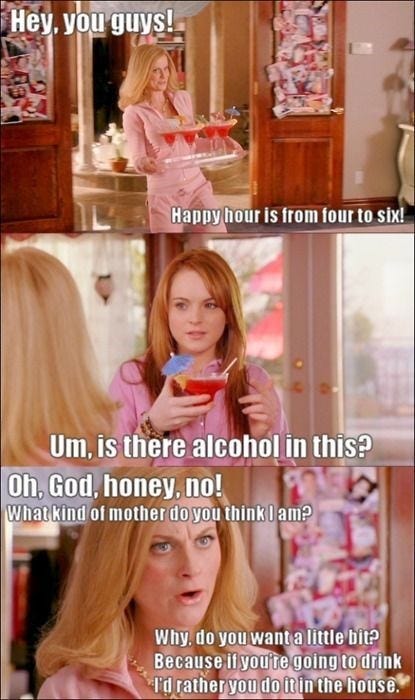

When I was in high school, my mother briefly mortgaged a home with its own private backyard pool. That home held a promise of normalcy and American delight, but the house eventually became a symbol for us of hard times. Before she sold it and got sober, I spent weekends on the deck, around the pool, smoking pot and drinking warm beer with girlfriends. My mom was a “cool mom,” which was a source of confusion and shame for me, but this also meant our pool became a gathering place, somewhere other girls wanted to be, and for that I felt lucky.

Since I grew up in California, it’s perhaps not surprising that I have an affinity for swimming pools. As a kid, I always used to loudly proclaim— the way kids do— that I favored a clean, chlorinated pool over the ocean, which stung small cuts on my knees and hands and left my bathing suit bottoms baggy with accumulated sand.

I also became addicted to (among other things) the sun— feeling high on the tender warmth of the Los Angeles rays, which shot down into the pit of my belly, just like that warm beer. And I learned to relish the energy of being near water, wet and lazy, flipping magazines like my mother, and sweating.

After I had kids, there wasn’t much time for lazing around pools, which were now inseparable from water wings and hyper-vigilance, but I still loved holding my babies in the water, bopping them around, watching their rapture as they smacked the water. I took them to swim whenever and wherever I could: at the local YMCA, on holiday getaways at hotels. And I dreamed that one day we would buy a home with a pool, a place where my kids would never feel cooped up.

I still live in California, so that dream didn’t pan out, but last summer, I entertained purchasing a membership to a local pool club. For the uninitiated, suburban swim clubs give paying families access to a privately-owned pool where members pay dues and perform volunteer hours. In our Bay Area suburb, I was shocked to find out, the first year of membership at most private swim clubs costs around $800-$1000. There are additional fees to get kids on swim teams or throw birthday parties at the facility, and in subsequent years, maintaining membership costs upwards of $500.

Our local city-run public pool, on the other hand, just down the street from our house, has day passes for kids and adults for a few bucks a day, so this summer, my family bought a season pass for the first time, and we fell in love.

There’s a distinct carnival aspect to the public pool: Teenage lifeguards and young aquatics managers run the place and DGAF.1 Everyone’s bodies are exceptionally exposed, but no one really goes to the local pool to size each other up or flaunt their thong bathing suits (except a few of those young lifeguards). There is very little posing of any sort, though there is lots of activity. Most poolgoers are old, or caregivers, or under eighteen, and there’s just nothing cool about it, which is what I enjoy.

The local pool takes everyone down a notch.

Over here is an old man doing a handstand under water repeatedly, as exercise. In the next lane, there’s an old woman doing walking laps in the shallow end, scowling at the splashy kids as she moves her foam weights through the choppy waters. Grandparents enjoy little and big kids, encouraging them to share rapidly deflating inner tubes. Tweens try to play it cool, but can’t help wrestling with siblings, dunking and splashing, and flipping over pool noodles.

Meanwhile, parents and aunts and uncles perch themselves on the edges of the shallow end, happy for a moment of peace while their kids thrash about. As the children practice ice cream scoops in the water, their grownups marvel at the breakneck passage of time and at how the kids have grown: once they couldn’t even bob under water without screaming in horror; now look at them.

There isn’t much magazine-flipping or sun-soaking at the public pool either. No one really goes to work on their tan, except that one lady up on the grassy knoll who’s been baking in her two-piece all day, smiling as she half-watches her kids from a distance, clearly thrilled by this new phase of motherhood.

Every few days, when the wind isn’t gusting too hard, the teenage lifeguards set up huge inflatables that they float out into the deep end. Big kids pay $2 for wristbands and line up by the pool’s edge, then they leap on the bouncy blowup plastic, pretending they’re on American Ninja Warrior as they swing on a rope that connects a slide and finally launch themselves down into the cool water.

This was the first summer my oldest kid could hop on the inflatables, and my four-year-old watched with me from our spot on the warm concrete, each of us laughing and cupping our mouths as big sister, dad, and a gaggle of teenagers ate it on the floating bouncy house, then tumbled into the pool, yelping.

Rising above their expressions of surprise, most of the other adults at the pool are also gently shouting—“big arms!” “blow out your nose!” “I saw!” For my part, I spend a good deal of my time at the pool distractedly laughing at all the adults belly flopping off the diving board. I’m not laughing at them, but with them. There’s something wonderful about seeing bodies of all shapes and sizes walking around half-naked, smiling and delighting in movement, testing the limits of what they can do, and acting like children.

I am not naïve enough to think that no one feels self-conscious about their body at the local pool. I often find myself quietly shaming my own motherly stomach, before forcing myself into the cold water, where I forget all about it. Being the fun mom, or trying— the mom who plays in the pool with her kids, who leaps off the diving board, channeling her twelve-year-old self, then over-explaining to her kids her short stint as a pre-Olympic diver in middle school— being engaged in teaching my kids how to side-breathe or do cannonballs makes me care less about what I or anyone around me looks like. We’re all just moving in a sterile sea of enchantment.

But community recreation has a checkered past. The Americana vibes I pick up off my local pool feel mythical because public pools were initially designed that way—to evoke a sense of community and solidarity. In her book The Sum of Us, Heather McGhee documents the racist—and largely forgotten—history of the resort-style American public swimming pools built in the 1920s and 30s.

“By World War II,” McGhee writes, “the country’s two thousand pools were glittering symbols of a new commitment by local officials to the quality of life of their residents, allowing hundreds of thousands of people to socialize together for free.” The public pool was envisaged as “an ‘Americanizing’ project intended to overcome ethnic divisions and cohere common identity.”

McGhee cites one county recreation director who thought a little like I sometimes do: “Take away the sham and hypocrisy of clothes, do a swimsuit, and we’re all the same.” But as desegregation laws went into effect in the 40s and 50s, McGhee writes, whites either stopped going to community pools where Black families were now welcome, or they converted public pools into private ones where only white people were admitted.

Many white city officials drained pools completely, filling them with dirt rather than share public space with their Black neighbors. Other pools erupted in violence, with white mobs surrounding and brutalizing Black swimmers. And in 1971, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Palmer v. Thompson that officials could close a public facility rather than desegregate, since “illicit motivation” on the part of the officials moving to lose the pool couldn’t be proven.

Mythologies around protecting white women from Black men informed much of the discriminatory culture at public pools. McGhee’s history mostly draws on events that took place at pools in the South and the Midwest, but she notes that racist attitudes around integrating the pools were widespread. I was curious about the California history in particular and found that the history of the Sutro Baths in San Francisco is also marked by racism, as is that of the Los Angeles bath houses and the “black Palm Springs” community set up north of LA, in Val Verde, by wealthy Black Americans who felt excluded by the California Dream.

That era marked the end of the large public pools that held such promise earlier in the century, but backyard pools and private swim clubs grew in popularity with white Americans.

Hollywood also developed an affinity for private pools, especially ones with men floating in them, dead or alive. In 1964, Dustin Hoffman dreamed of sex and found it “very comfortable just to drift” in his parents’ pool after graduating college. And in 1974, the film version of The Great Gatsby restored the 1920s image of the palatial pool as a symbol of wealth, success, and class conflict.

When I was a kid in the 90s, pools in film were usually linked to rebellion: sexy pool time in Wild Things, parent-free parties in Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead. And to have a pool of one’s own meant one had made it. The private pools I frequented mostly belonged to friends’ parents and were where, as an adolescent, I learned to don a bikini, suck in my stomach, and drink.

But for most Americans, private pools remain a symbol of carefree luxury—of slowing down, of disconnecting from public life, of leaving the world behind or refusing to return to it. The community pool, on the other hand, begs engagement—for laps or teaching kids the backstroke. Some parents, I know, find this less pastime, more labor. But I, who will never be the cool mom, accept the invitation to play.

The demographics at my local public pool roughly reflect that of the suburban Bay Area city where I live, though the mix of pool goers is more diverse than the mostly white population, presumably because those who can afford to swim elsewhere, do.

As a white woman though, I often wonder whether the joy of community I find at the public pool is just a false flag—a fabricated sense of collectivism that makes me alone feel good, without my actually doing, well, anything but floating around. I wouldn’t be likely to experience fear or violence at the pool, unless it were sexual. It is the sex-less-ness of the public pool that is for me, at least in part, so attractive, but that doesn’t mean that people in my community don’t feel comfortable there and therefore never show up, or that still others can’t even afford admission.

But as my kids pile on each other and on friends from school in the water—friends who speak different languages at home, who have different skin colors, who live all over the city—as they play with friends they’ve only just met and will keep for just an afternoon, as they chase inflatable beach balls, torpedoes, mermaid toys, and the odd piece of trash, coming up with new games that don’t make much sense to me, I feel more connected to my neighbors.

At the grocery store, I’m usually irritated by crowds and carts. But at the local pool, I work hard to push aside my tendency to be annoyed at sharing public space. I track the flight of the toys we brought to practice swimming down deep, as kids we don’t know snatch them up and ferry them toward the deep end. I know my inclination to hoard resources isn’t something I want to pass on to my children, and I admire for a moment my own willingness to push past those instincts, feeling hopeful that I will raise kids who will be more intuitively generous than I am.

When my kids exhaust themselves, they lay on the warm concrete, and I cover them with towels. My youngest could hang in the sun and watch people play all day, munching on chips and fruit, learning the pleasures of heat and voyeurism. I am glad that he is watching. I want to render visible for my children the work of community and the work of sharing public space, but also the joy—the pleasures of finding enjoyment with strangers.

There are moments when the promise of the American local pool feels within our reach. Then, of course, my phone pings, and that man with the beard, I decide based solely on appearance, is definitely alt right, and someone at a nearby picnic table is talking about Dobbs and I can’t tell what their stance is. My nostalgia is splashed in the face by the history of everything, and I feel sweaty and uncertain of myself. It’s 95 degrees. Summer can’t last, I know, and I suppose it shouldn’t.

This summer, I did catch one of the lifeguards, a lanky teen, hastily jump in the pool after blowing his emergency horn. A girl and her brother had been playing like they were drowning, and the poor lifeguard was visibly rattled and completely embarrassed. I nearly applauded him, but instead, I wondered for far too long what he told his friends and family at the end of the day.