*some spoilers!

I spent most of my early years parenting lamenting Barbies and arguing with family members about their super gendered desperation to fill my toddler girl’s room with dolls. I was hesitant about seeing Barbie. I get that Greta Gerwig is a) cool b) smashing glass ceilings c) just as feministy as I perceive myself to be and one can safely assume she took all the history around dolls into account while making this movie duh. I knew this film wasn’t going to be a translation of Barbie’s original ethos, but a kind of conversation with it, a contemporary update.

Going into the movie, however, I still had plenty of questions: How is this movie something other than empowerment/girlboss feminism? What does this movie have to say about the limits of centering work and careerist ambition in the feminist movement and/or about the limits of representation as liberation? Is this just a fun white feminist movie or ??

Most of all, I was curious about what’s going on with moms in the film—and, like, are we just cool now with our kids playing with Barbie!?

I had questions, but what really led me to just take my 8yo daughter to the PG13 movie already was how much conservative men hate this film [not linking here to the 43-minute Ben Shapiro tirade against the movie or Ted Cruz calling it “communist propaganda” even though he admits he didn’t see it]. I also spent way too much time scrolling Common Sense Media reviews of the film, many of which suggested I protect my child from “racy parts” of the script about gender equality and patriarchy.

Most notable apparently to many parent-reviewers is a scene in Barbie in which little girls comically bash their baby-dolls in protest against role-playing as mothers day in and day out. I figured I’d take my 8yo daughter anyway, and write a bit about how this film is perfectly fine, great even, for younger kids. In our house, we’ve discussed many of the “sophisticated themes” that come up in the script already, and my kids both unfortunately have a pretty full curse word vocabulary lately. I’ve written before about how conservative panic over kids’ supposed overexposure to “woke” culture is just a projection— a defense against the many ways in which white hetero patriarchy grooms kids for gender roles from a young age. So I assumed I’d see this movie and write about how it did not in fact go over my well-raised feminist kids’ head.

Watching the film, I was instead reminded of how young my daughter still is, and how much of the adult world still seems so strange to her.

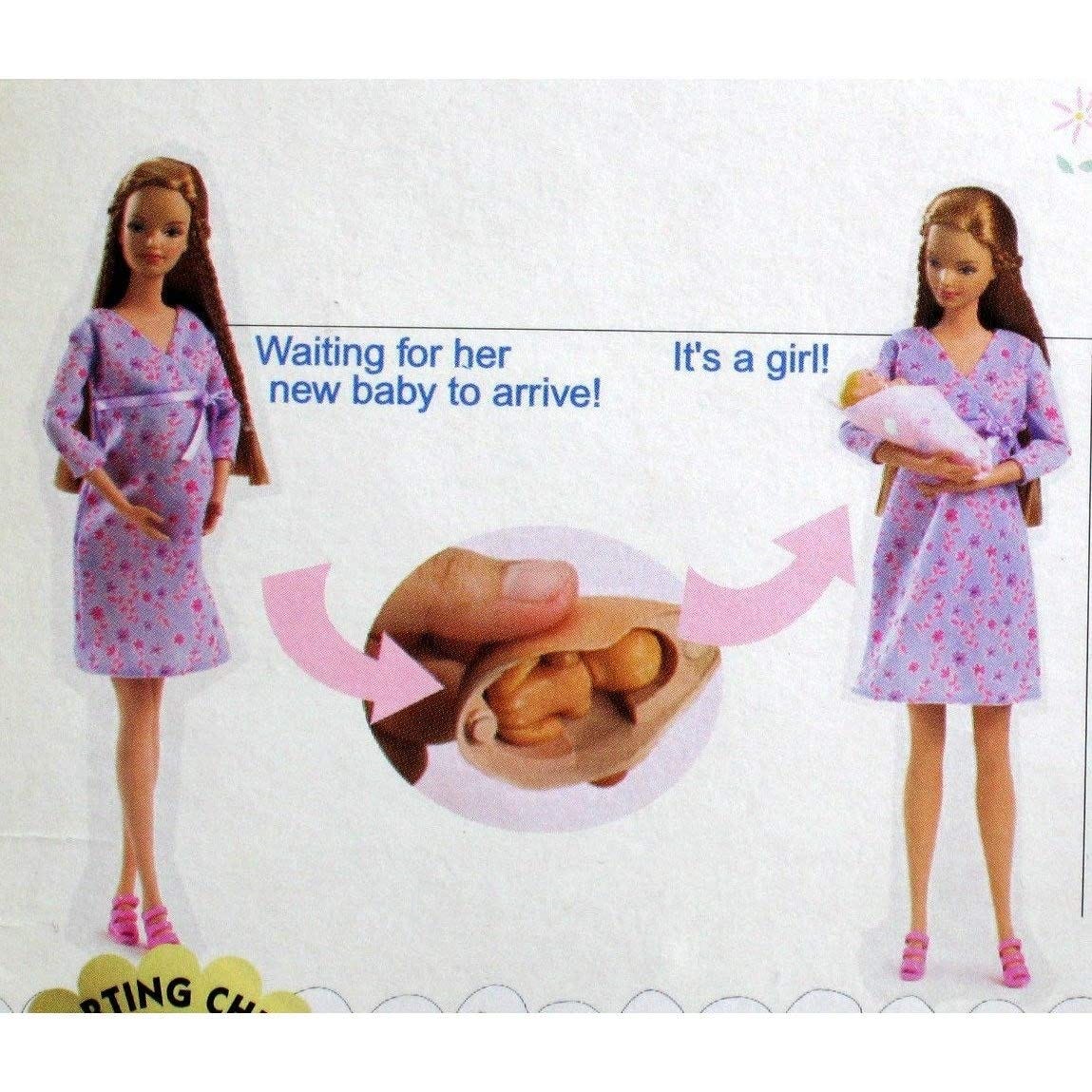

Barbie has notably never been a mother, something the film underlines via the short-lived pregnant doll Midge’s cameos. Midge often stands off to the side, gets shoved off-screen. In Barbie, however, motherhood remains a central theme. It’s one of the many unfinished problems of feminism at which the film continually winks. When the film begins, Barbie—despite transforming over time from pointy-boobed sexpot to a catalogue of aspirational identities for girls—has not solved or fixed the real world, and this cheeky opening acknowledgement gives the film both its levity and gravity.

Gravity because— it’s confusing, right? Girls can be anything! But women cannot.

Watching the film felt much like entering a child’s world, in which girls are expected to hold both of these statements with equal weight. Barbie opens in Barbie Land, a girl-boss utopia where women rule the world, every night is girls’ night, idealism and empowerment are the guiding logic, and kindness and goodness are always in conflict with the vague, contextless problems of the “real world,” which continually threaten to ruin the fun.

When Barbie Land was punctured in the film by Barbie’s sudden preoccupation with questions about death, I noticed my daughter stiffen up beside me. Her childish world, too, is so often cracked open by questions like these, the kind that float in from the adult world. Like the dolls in Barbie Land, kids don’t understand sex, love, or death, even if they play at them. In childhood, as in Barbie Land, everything is experienced without context, with bits of information missing.

In childhood, as in Barbie Land, the idealism on which we open cannot last. Barbie’s feet can’t stay pointed forever. Reality creeps. The center cannot hold.

In the film, there is a clear but undefined separation between Barbie the doll and the girl who plays with her, and imagines with/as her. Humanness begins to interfere with the “solved” world of Barbie Land though, launching the plot and high jinks of the film, but also some of its bigger questions about how to make sense of this iconic toy, which has been both revered and reviled by feminists since it launched half a century ago.

As Barbie Land destabilizes, Barbie is threatened with the possibility of (gasp!) cellulite— a terrible fear to contend with for this perfect girl-object. My daughter has no idea what cellulite is because it’s not something anyone in her life frets about out loud. But I could sense, because I am her mom, that she shifted again in her seat while the term kept coming up. She knew enough to make out that “cellulite” had something to do with women’s bodies— the way they look for real, and the fantasy to which we hold them.

Like childhood, Barbie Land is a world constructed in part by adults’ ideas about the world—corporations, cultural references, gender ideology—but also by children and their fantasies. The Barbies may start off thinking the real world is “fixed,” but as Barbie is forced to venture out in to the real world, she is catcalled in Malibu while rollerblading. She senses the “undertone of violence,” even though she doesn’t have a vagina. While Barbie Land is a world of female power, the “real world” is disappointingly the inverse.

No one in the film, however, can quite explain the relationship between Barbie Land and the real world beyond that— are they connected by imagination or is Barbie Land “like a town in Sweden”? They also can’t quite name what Barbie’s purpose is for girls anymore. Throughout the film all the Barbies, and a few humans, are seeking, but not finding, any “definitive” take on Barbie or her confusing brand of feminism.

My daughter also didn’t know that Mattel is the company that makes Barbies, because we don’t own enough of them for it to come up, but the corporation is its own character in the film, so at some points I found myself leaning over to whisper explanations about what was going on. There ended up being plenty of references in the film that my feminist daughter didn’t get. I have spoken with her at length about the history of gender relations, about the terms patriarchy and feminism. But my daughter, slowly nearing the precipice of tweendom, doesn’t yet know what capitalist sexualization is, or fascism. She doesn’t really grasp how male power plays out in professional settings, or why the Indigo Girls matter, much less why the Kens love to explain everything and play guitar at Barbie for hours. She hasn’t heard the term male fragility, and doesn’t fully grasp the association between men and war.

For me, none of that was really what the film was about anyway, even though Gerwig does some very funny and clever things with all those subjects. It’s really a film about motherhood and girlhood, about growing up and growing apart— about mothers and daughters losing each other when girls come to understand the world they will age into and how hostile it is towards women. It’s a film about no longer being able to inhabit the fantasy world we once shared with our moms. Parts of it are funny, others are utterly heartbreaking.

Did my daughter know why I was clutching her during the scenes of little girls playing with their moms and then, years later, pushing their moms’ hands away as the they aged into that discomfort that comes with being a teen girl?

I don’t know. About halfway into the movie, I stopped trying to explain every part of the script to my daughter. I was crying, but also, I wanted to allow her that state of not knowing a little longer—not to protect her, but to allow her to come out of her fantasies and into the harder parts of the adult world in her own time. I hoped she understood that the film centers around a mother and her daughter, each trying to return to that once-shared dreamland, where every girl can be any woman, and where male power doesn’t exist to hurt them. But it didn’t really matter. We laughed at the jokes we both got, and held each other tight when things got real.

During America Ferrera’s much-talked-about monologue about how exhausting it is to be a woman, my daughter snuggled up to me as she might in the most frightening part of any film. This we both knew was real, she sensed that much, even if she lacked all the details needed to understand. She clutched me now, and I could feel the continuum ripping as I’ve felt it rip before, during every one of our hardest, most meaningful conversations.

At one point, Barbie blames Ferrera’s character, the mother figure, for the pain of entering the real world— the pain of being human, of growing up, of leaving the fantasy behind, which the film argues is why humans turn to power structures like patriarchy. But it’s a daughter and her “weird dark crazy” mom who wind up saving everyone by articulating what it’s like for women living in a patriarchy.

The film does not “solve” patriarchy or the intractable cultural legacy and cipher that is Barbie, anymore than it solves the problem of where mothers fit into Barbie’s careerist empowerment stories. The film, too, is wrapped up in its own consumerism, even as it critiques it. But the filmmakers have fun with all this knowledge and make the case that Barbie is an idea about women, and it’s telling she continues to be such a battleground.

Toward the end of the film, Barbie says she doesn’t feel good enough for anything, tapping into that voice women carry with them, set as they are against so many impossible standards. My daughter whispered to no one and everyone a protest: “That’s not true!” she said vehemently. Correcting Barbie’s inner critic.

And when the film ended with Barbie making a decision about whether she wants to live in her fantasy world forever or face the pain of being human, my daughter still wondered about Barbie’s decision to be real. In many ways, my daughter still prefers the world that tells her she can be anything.

“I wonder what would happen if she said no,” my daughter whispered.

And I said, trying not to puddle up in tears, “She’d never grow up.”

God I love your brain. Thank you for this. Spot on and brilliant as always.