The internet has been abuzz with discussion of “quiet quitting.” The term is a bit of a misnomer: no one is quitting. They are just coasting at their jobs and expressing on social media their dissatisfaction with white-collar striving. But the concept got me thinking about how one might “quiet quit” maintenance labor—all the work we do in our homes to make our public-facing lives possible. What would it mean, for instance, to “quiet quit” housework?

I’ve written a few times about messy moms and the late 2010s embrace of parental disaster. That discourse of mess rarely situated the unmanageability of the home and American motherhood within any economic or political context. But talk of housework— and the abandonment of it—has since shifted substantially. Many mothers are throwing in the towel when it comes to folding towels.

Mothers have been vocally “quiet quitting” housework ever since the pandemic began. In a recent piece for her Double Shift newsletter, Katherine Goldstein argued that our obsessions with “Instagram perfect homes” and self-sufficiency are hurting our friendships. “Letting people see your messy house,” she wrote, “shows vulnerability.”

Books like Eve Rodksy’s Fair Play and Kate Mangino’s Equal Partners have also brought the highly unbalanced, gendered division of labor in the home into greater public consciousness. As a result, in recent years, conversations regarding housework have become more nuanced, more politicized, and more feminist—perhaps one reason for increasing tradwife content, but that’s for another post. “Household gender inequality is a broad social problem that is passed from generation to generation, and the ramifications are harmful for everyone,” Mangino writes in her book. “Household inequality is not an individual’s problem or even an individual family’s problem.”

I have been quietly “quiet quitting” housework for a long time, with varied results. When I was depressed in the early years of motherhood or during the height of the pandemic, doing the bare minimum came naturally. It was all I could manage. Now, I get overstimulated by mess. Not folding laundry only leads, in our house, to parents and kids digging half-asleep through a clothes hamper during the morning rush, which makes me feel neither more powerful nor freer.

But I admire those who can let mess pile up at home as a small, intentional act of rebellion. I am always reminded of Melville’s character, Bartleby, when I think about moms resisting housework. Bartleby refuses, without explanation, to participate in his work. In her book Ugly Feelings, Sianne Ngai argues that Bartleby is a figure of “conspicuous inactivity,” which makes him more powerful than he initially might appear. Suspended action of this sort highlights the limits of agency, whether in an office or kitchen, and an attempt to assert some agency nevertheless.

When we quiet quit housework, there is none of what Ngai calls “high drama.” A messy house may not feel like a radical gesture. For one, it is an individual form of resistance, visible only to those who visit the home (or see social media images of it). Small acts add up though, and we don’t have to choose between grand gestures and tiny rebellions.

Letting friends see your messy home might cultivate a deeper intimacy and soften gendered cultural expectations. It might even be a temporary move, one that inspires larger conversations and shifts in the home, which can in turn have effects on women’s ability to show up in public life.

Refusing to tidy up around the house is not, however, likely to dramatically change the conditions that make our lives so unmanageable in the first place: hyper-consumerism, limited leisure time, overwork, misogyny and racism, the cultural and political denial of the work on which all other work rests.

But another reason it feels only mildly radical to refuse the work that has long been extracted from women without pay for so long —the invisible labor churning the more visible wheels of capitalist production—is that we don’t see the home as a site of social revolution, even though it so often has been.

Conducted on a much larger and more organized scale, collective strikes against housework have been effective in challenging gender norms within the home and in shifting both policy and social attitudes about gender and domestic work.

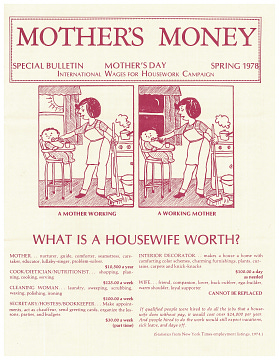

In 1999, the International Wages for Housework Campaign launched the Global Women’s Strike, demanding “payment for all caring work—in wages, pensions, land and other resources.” The global campaign, still active today, built on the foundation set by the Wages for Housework movement, led by Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, Silvia Federici, and others. Wages for Housework also advocated for payment for “women’s work”— housework, but also sex, mothering, emotional labor.

The movement was both practical and ideological. Getting paid for work performed in the home was an explicit aim. It was also a radical perspective meant to illustrate and challenge how the housewife serves capitalism and patriarchy (a role tradwife content warps and affirms). As Federici wrote, to remunerate women’s work, everything would have to change.

Strikes are crucial to labor movements because they do what many women are trying to do now, online or alone in their homes, as they renegotiate unequal divisions of labor: A strike makes invisible work visible; it makes the absence of an essential worker seen and felt.

This is not to say that smaller efforts to change interpersonal attitudes around gender, sex, marriage, and domestic labor are not important— they are. But when a culture exploits an entire group as aggressively as women are being targeted today, walking out on the job has often been the best method of revolt.

In 1975, 25,000 Icelandic women went on strike in Reykjavík, refusing to work both professional and domestic roles. Men were forced to take children to work. They fed the kids sausages and candy to get through the day. The strike highlighted how central women were to the economy.

“When women stop,” the Icelandic slogan went, “everything stops.”

One year later, Iceland elected their first female president.

“But how can you strike if you can’t risk being sacked or endangering those you care for?” Selma James has written. “This has always been the dilemma, especially of the carer on whom vulnerable people depend.”

In a recent piece for Bloomberg, Sarah Green Carmichael argued that women should go on strike at home, rather than in the streets, by refusing to do any more housework this year—since they do on average 5.5 more hours of housework a week than men, not including childcare, grocery shopping or errands. Carmichael also proposed “Equal Housework Day,” a tool for educating the public about the persistence of gender inequality in the home.

A day devoted to educating the public certainly couldn’t hurt. As Carmichael notes, many studies show that men think they are doing more at home than they are. But I favor Carmichael’s “nuclear option,” which is a cut above doing the bare minimum: “Leave the house messy and the fridge empty from now until 2023.”

Of course, mothers quietly quitting or pausing domestic duties at home won’t be enough to free us of forced parenthood and criminalized pregnancy, or to advocate for paid domestic workers who are still fighting for basic protections. But as the “quiet quitting” folks note, wage theft is alive and well, and nowhere is stolen labor and time more prevalent than in the home, which affects those doing paid and unpaid domestic work.

As we step into an era when my generation will have fewer rights than our mothers, the question of who will keep up the home as we fight to secure rights to our bodies is nothing short of urgent. And in these small strikes against housework, a revolution is brewing.

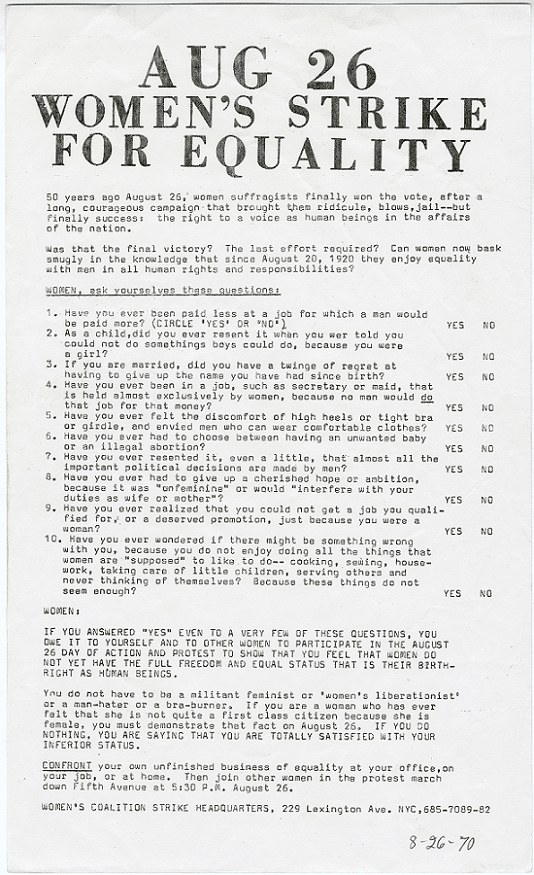

In the U.S. half a century ago, the Women’s Strike for Equality led to the institution of Women’s Equality Day on August 26, which we “celebrated” last week, even though women are far from equal today. Feminists marched in 1970 for what we should be striking for today: abortion on demand, free childcare, political rights, equality in and out of the home.

This flyer illustrates how little has changed, and how much we still have to fight for:

If you want to talk and write about the kind of collective joy you experience in the streets and in community — or about personal pleasures—I am teaching a class on that very subject at Corporeal Writing, starting October 20! The class is entirely generative and fully contained within the two-hour class blocks. No outside reading, writing, or workshops. In class, we will read a bit together, talk craft, then write in response to prompts. This will be a great way to generate new material, connect with fellow writers, and consider what representing hope and pleasure on the page means in this often grim era. Register here.

I am also teaching a reading and writing class on Silvia Federici for Hugo House. The class will blend theoretical discussion of Federici’s writing with somatic writing exercises, as we consider creative responses to the ideas proposed in Federici’s essays on bodies, sexuality, families, capitalism, witches, and more. Starts November 21. Register here.

And if you’re working on a memoir and have no/very little material, or a bunch of material that feels disorganized, I’m teaching a class for Writing Workshops on finding your memoir’s form. It will be super generative and a great way to organize and plot your project. Starts October 4. Sign up here.

If you haven’t yet signed up for a paid subscription, do so by the end of the week when the back-to-school special will disappear! As a paid subscriber, you will get access to community, extra posts, and a monthly digest of reading and watching recommendations from me.

Later this week, paid subscribers will also have access to a thread on housework, which will compile resources for big and small strikes, including Day Without Us, coming up on Sept 30, which I discovered while writing this. See you there.

Oof. This was difficult to read (an era when we have less rights than our mothers) and watch (that housewife tik tok was frightening!) I definitely have noticed that I am letting more messes go in my house in the last several months. I have been doing some personal work on unhitching my identity from having a clean house so I guess I've done some quiet quitting as a result. One thing I was thinking about this morning was how my husband never seems compelled to "pick up after me" in the same way I do about his messes. It really caught me off guard to realize how normal it is for me to pick up after him and how that is not something he would ever put up with for very long. It always surprises me when I see my conditioned responses in this way.

Also wish we had striked again on the 26th!

Thank you for this interesting and thought provoking concept. I heard about the 'quiet quitting' movement on BBC radio the other day just before your newsletter arrived, but hadn't thought of the idea in relation to women's domestic labour. Fascinating discussion, thanks : )