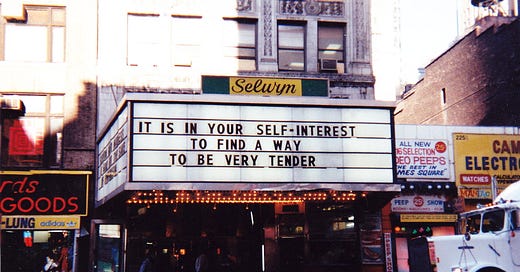

Welcome to part one of Love Language, a week-long series that explores the worst (best?) cliches of modern dating TV, and their broader cultural and political ramifications. You can read the introduction to the series here. If you want some fun memes to go along with all this, come find me on my Instagram.

Regular Mad Woman Readers: This series will arri…