Women Reclaiming Themselves from the Culture

Archiving and undefining sex, the harassment of public intellectuals who are women, lost feminist knowledge, and books about madwomen

This week I watched The Disappearance Of Shere Hite, a documentary that traces the mostly forgotten legacy of Hite’s research of female (and male) sexuality. The documentary also explores media harassment against Hite in the wake of her pivotal research on gender and sex, and her eventual ousting from American publishing.

In one interview featured in the documentary, Hite is asked whether she feels her research— which began on women’s pleasure, then turned to men’s views on intimacy, then led to a third book on love—is dangerous.

Hite replies, “equality doesn’t seem dangerous to me.”

Hite’s desire to understand the details of sex and sexuality, however, was perceived by many others as dangerous. Her three major works, published over a ten-year period spanning the mid-70s to mid-80s, inspired a storm of controversy that took a heavy toll on Hite’s health and well-being. Once enthusiastic publishers started ignoring her when she refused to go along with entrapment-style interviews. As she told reporters during that difficult time, the way men approached her book on public stages proved one major finding in her work: women want to be heard by the men in their lives, but they’re repeatedly shut down when they speak openly and honestly.

I can’t help but feel a kindredness with Hite and a deep admiration for what she put herself through in her desire to understand how both women and men experience their sexual lives. I’ve spent most of 2024 so far talking with women (and some men!) about their experiences with sex. Since Touched Out was published, I’ve received tons of messages from women sharing intimate details about their romantic lives. One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned through all these conversations is that women so often feel they are alone in their experiences, but they’re not.

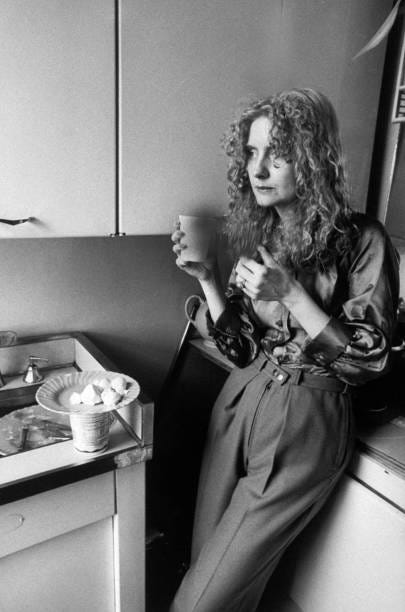

Hite was deeply uncomfortable in academia—another element of her life where I can easily project myself— and turned to modeling early in her career to make an income, using her appearance as currency to gain some money. She remained throughout her career interested in glamour and the power her feminine looks afforded her, but she quickly grew uncomfortable with her own objectification as a model, or what she called her role in the “pleasure machine.”

Trying to “know yourself, not your role,” she said, is “hellishly hard.” She pivoted to sex research soon after.

The cultural loss of Hite’s work—and of hard-won feminist knowledge generally— is one of the major points of the film. Hite’s work was crucially important, but now is mostly forgotten. Her research, which she conducted through a widely distributed survey, differed from other major sexologists of her time, like Kinsey and Masters and Johnson. As Hite pointed out in interviews, M&J gave the clitoris some attention, but in their later work reverted back to the old Freudian belief that healthy intercourse required male penetration.

Her research, on the other hand, found that 70% of women didn’t orgasm from penetration.

Another significant finding: many women were doing “anything to get [men] off” as quickly as possible, not really enjoying the sex they were having.

Years later, in her study of love, she found that only 13% of women felt love after being married more than 2 years.

More than anything, Hite wanted the public to take these findings seriously— to meet them with empathy and curiosity. What women were saying suggested to her they had been adapting their sexual experiences to male bodies for centuries. It was time for a change. She argued that what was needed was a redefinition of sex (or “undefining”), though she didn’t want to limit what that redefinition might look like.

In response to her work, male pundits and critics who feared their own irrelevance (though this wasn’t part of her argument) verbally attacked her in the public domain, shaming her on TV, and tearing apart her arguments, often admitting they hadn’t even read her book.

When she published her followup book on male sexuality, and shared her research once more in the press—her research showed men felt lonely and disconnected, sound familiar?—pundits and critics balked at public conversations about intimacy and masculinity. In one terrible media stunt, Hite was forced to sit on a talk-show stage surrounded by angry men who took turns yelling at her—the show was Oprah.