Who Are You, Really?

On Severance, the ideal worker, numbing out, and our precarious selves

I’ve been away from the newsletter for a few weeks while working on my book, and I hesitated to return this week. It’s always hard for me to get back into the swing of a particular form of production when I have been entrenched in some other form. Shifting gears, whether from non-work to work, or from one type of work to another, brings on complete dread. Often, my body just grinds to a halt.

I value the writing I do here, but it’s the volume of work required to make a life, to secure an income, to invest in things that feel like they could matter or pay off, but you’re just not sure, that makes re-calibrating so rough. It’s living in a world in which the body is best understood by machine metaphors, like those I use above.

My oldest kid is also home from school this week for her break. Yesterday, I retreated into the bedroom to read something on my phone because she wanted to play a TV show theme song on repeat; who was I to ruin the fun. Later, she cuddled up beside me on the bed to pet the cat, whispering and rubbing its belly. I thought of all things I should be doing other than enjoying this motherly moment, lazing around like I used to with my baby, who is now, quite suddenly, so big. I tried to rev myself up for some work.

I had planned to write about heavier things this week, but I decided, there on the bed, that they felt just that: too heavy to take on with a kid in the house constantly popping in and out of frame, humming in the background. Writing about hard things while being asked for snacks and attention isn’t new to me, but I knew it would just require too many hard shifts. With my kids back in school, I’ve gotten used to severing my work self from my mother self a bit more, and although I resist the patent separation of women’s work from writing, sometimes it’s just easier to live in two worlds.

So, this will be an essay about Severance, a show I started recently after spending one too many nights on the ton with the mamas of Bridgerton. In this gathering of words, I will attempt to convince you that my analysis of Severance has an important place here, in a newsletter about motherhood and care in America, in an effort to make all those hours I spent watching the show count for something. Only very mild spoilers.

I’ve been into shows lately, staying up too late, burning through them with little guilt. The practice is not restorative, though I still wade into it like I’m sinking into a bath. I occasionally convince myself I’m being productive, inhaling whatever new streaming series, feigning interest in some piece I might write, but probably won’t, because I’ll spend too many evening hours watching shows.

I definitely do that “revenge bedtime procrastination” thing, though I have a sort of vehement knee-jerk reaction to that term, since I stay up late very intentionally, very calculatedly. I’m not putting anything off. I’m just enjoying the moment! It’s even better when my husband and kids are all asleep and silent. I did used to think of this practice as retaliation against the system, against work, against my lack of free time, especially when I stayed up drinking. But now: I’m just alone, and I want it to last forever.

The reason I watch shows, however, is to sever my work self from my after-hours self. Since I quit drinking, my evening rituals have become even more of a life raft, because I no longer have alcohol to mark the transition from one part of consciousness to another, or to deaden the flare-ups in my body that come when the workday inside me just won’t die. I need to burn a different world into my eyes to come down. So, I bedeck the couch with chocolate and fruit and a flask of water. I don’t dive into anything until the kids are sound asleep or I’ve very vocally clocked out of motherhood for the day and handed over bedtime duties to my spouse.

Recently, I’ve felt a special giddiness for new episodes of the 2010s startup fail shows—The Dropout, Super Pumped, WeCrashed (these titles, though?). The antiheros in these shows are basically bad people, and yet I identify with them or at least care about them enough to keep coming back. I’m all for an unlikable character, but I think the special appeal of these starry-eyed young capitalists is for me more millennial misadventure, along with some gratitude and self-righteousness. I feel thankful, watching them, that I didn’t go to business school or try to make it in Silicon Valley, which soothes years of wondering whether I might have fared better if I had.

These shows are all kind of gig economy versions of American Psycho, without the murder. Everyone is sick with capitalism and neoliberalism; you nearly feel for them. They think they’re going to change the world with their “important” car-sharing apps and co-working spaces and blood test tech, and they embrace without hesitation the idea that they can do good and get super rich at the same time. Their naivete feels laughable now but was such the vibe then—this idea that technology might save us from work, give us more space to be ourselves, make the world better. In some corners, the vibe is still there.

Which brings me to Severance, a world in which you can get a computer chip implanted in your brain to divorce your work-life self from your private-life self. In such a world, technology frees employees from the workday. The separation between private and public spheres has literally been embedded in the body. When off the clock, severed employees never even have to think about work—they can’t even if they want to. The technology is such that “innies” (work selves) and “outies” (off-the-clock selves) cannot communicate and know nothing about each other.

Everyone in the Severance world, in other words, is sick with the illness of work, but in response, they’ve volunteered for surgery. It seems extreme, but they’ve just followed the false pursuit of work-life balance to its logical end, chopping themselves into two versions of the same person.

I have written before about how waged work relies not only on unpaid care work—housework, mothering, caregiving, elder care—but all the invisible maintenance labor we do to remake ourselves for the workday. In many senses, we already do what they do in Severance, without the brain surgery. We often completely dissociate our personal lives from our professional lives to fit the mold of the ideal worker. Even if the pandemic has arguably exposed the fallacy of this splitting of the self, many of our most basic institutions and mythologies still rely heavily on the separation of the work body from the home body.

Consider, for instance, the image of the writer at work, unencumbered by home and family, severed from familial and domestic duties, as well as the basic reproductive labor He must do to maintain Himself (I’m thinking here of Jenny Offill’s observation in Dept. of Speculation that Nabokov didn’t even fold his umbrella or lick his stamps). Even though I think about the false and problematic nature of this image of creation constantly, when I sit down to work with kids or mess all about, I’m troubled by the desire to cut motherhood out of me so I can work, and not because it’s the only way to create—it’s just the only way to create in a world that expects one’s output to look as though it’s written by someone without a body or a life.

[My daughter just hollered from the other room, btw, “I’m going to make a banner!” (?)]

In Severance, uninhibited by their personal lives and basic reproductive labor, severed employees can focus exclusively on their work. They’re living the dream. Lumon, the company in Severance where all the severed workers work, is also uninhibited as a result: Lumon surveils its employees, but also rallies everyone unironically around work-family, hokey office culture, legendary CEOs, wellness initiatives, and endless maxims. The “break room” is literally a torture chamber, the halls are labyrinthine, and over time, the employees begin to question whether the company even produces anything, so mysterious is the nature off their work.

The best moments in Severance, however, don’t come from Lumon’s blatant exploitation of its dehumanized workers, but rather in the scenes that signal how, even with such advancements in tech, the work self still cannot escape the apparition of the life lived beyond the office.

Coworkers discuss feeling out their mouths, teaching each other how to check what their outie has been up to in the after-work hours. Mark, played by Adam Scott, sometimes has red eyes at work. We learn this is because his outie has been in mourning. Later, when outie Mark finds bruising on his hands, he says he’s been told he jammed his hands in a water cooler at work. He’s skeptical.

One innie gets a rare opportunity to see a video of his outie, who mentions that while he doesn’t know the nature of the work the innie does all day, he knows he comes home feeling “tired and fulfilled.” But Helly, the rebellious red-headed Bartlebyan worker played by Britt Lower, uses the bodily connection as leverage: she tries to turn on her outie, threatening to cut off her own fingers.

Helly eventually helps lead the office team on their quest for answers—they want to know whether their work is “important,” echoing a word that carries a lot of weight in those 2010s startup shows.

Without shared consciousness, the only overlap between the work selves and non-work selves is the body. And as the innies and outies become increasingly curious about their other selves and the nature of their work, their shared bodies get more beat up, more haggard. The ever-widening gap between the waged worker and the reproductive laborer—and the strange inability to locate which self is the real self—overwhelms everyone.

Who, after all, is the real you, the immobile person on the couch at the end of the day or the person taking the meetings?

Perhaps love might be some key to locating the true self. Some characters in Severance speculate whether love transcends the severing process. A few plot points indicate that maybe it doesn’t.

But one severed worker has a child on the outside who he accidentally meets when things go awry. The vision of his child—and the tenderness of a brief, accidental hug—rattles him deeply and eventually comes to a head during a milestone work dance party. The knowledge of his family radicalizes him.

In a few other scenes, there are suggestions that some mothers may sever themselves just during childbirth, which recalls the history of twilight sleep.

The duality of self in Severance makes the show compelling, because ultimately the duality cannot hold. But I found myself wondering how the story would fold in on itself if, rather than giving the workers full-time jobs, it considered contingent work, or maternal labor. Maybe it’s going there?

If I were to separate my work self from my many other selves, there would be too many tiny parts. What would even be left, what would feel whole? I work, currently, for four employers, not counting those I write for. How many work selves do those of us who juggle multiple part-time jobs really have? How many selves do mothers or other caregivers have?

As Darcy Lockman notes in All the Rage, mothers who work outside the home contend not only with the fantasy of the ideal worker, but with the image of “the ever-present mother.” If the childless worker seeks to balance work and “life,” the history of the double shift suggests that mothers have at least three selves. In practice, it feels like a lot more.

I’ve become more attuned during the pandemic to the violent fits my nervous system throws when some self is overwhelmed or at odds with some other self, or when I’ve just cut myself up into too many parts trying to do too many disparate tasks or wear too many hats. When this happens, I usually try to shut everything off in front of the TV.

As a girl, I did the same thing. I remember watching TV in adolescence, staying up after my bedtime to watch Nick at Nite, or turning on MTV in the afternoons as background noise while I did my homework, so I didn’t have to think about heartbreak, feeling used by boys, having no boobs. Escapism and even “numbing” don’t quite capture what I was doing, or what I do now. I have often used TV to turn my body off and to be someone else, but I never really get away.

During the pandemic, I came to terms with the physical aftereffects of the hyperfocus I bring to my writing, and of my empathic sensibilities, which keep me up for hours after teaching and other social interactions, as I slowly drain other people’s faces and comments from my mind. I have learned that when I’m angsty about the kind of mother I’ve been that day, or feeling as though I’ve become simply a body meant to serve the other bodies who circulate in my home, knots take up residence in the pit of me.

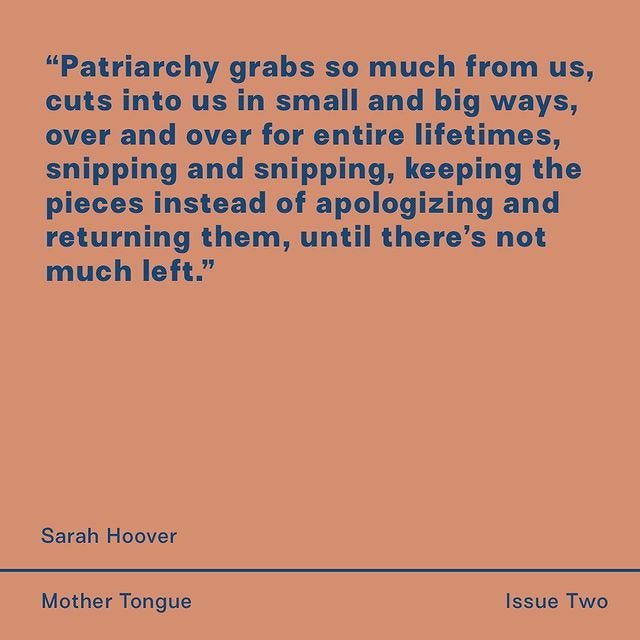

Basically, I’ve come to see I have many selves, all of which wreak havoc on my body, and it’s a challenge. This quote comes to mind:

The self is naturally prismatic, I think. An amalgamation of body and mind and everything we’ve encountered in the world. But we live in a time that cuts us up with intention, and asks that we do so to ourselves.

I don’t know which of me is my truest self. If pressed, I’d say it’s my writing self, because only there can be everyone. But there are times when it’s my motherly self, my isolated and indulgent self, my other work selves, my outdoorsy self... In any case, I’d like to think we don’t really have to choose. But now I must switch gears, as they say, and go make lunch.

So true--I love that even in speculative fiction like Severance--which I love--we are still made to wrestle with only inner and outer selves, public and private spheres which are artificial, victorian, and yet still governing our bodies, our work, our care. The many, many selves is something that we need to somehow make much more space for--or at least to recognize and stop trying to force people into yet another binary....

This is so, so good. I'm only 2 episodes into Severance (busy watching Better Things, the new season of Atlanta, My Brilliant Friend and Pachinko) and this is the commentary I was searching for on the internet at 4:30 am this morning when I finished the 2nd episode. I revel in my obscenely early quiet time, relishing the solitude and the escape into my tv worlds before heading out to commute, teach, exercise, pick up my kid, make dinner and do it again. Thank you for articulating -so clearly and beautifully- much of what I've been thinking about and feeling.