Towards an Economy That At Least Makes an Effort to Pretend It Values Maintenance Labor

On essential work and the drag (and pleasure) of reproducing ourselves

Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ “Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!” outlined a proposal for an exhibition called “CARE,” which would “zero in on pure maintenance, exhibit it as contemporary art.” The show had three parts: Ukeles would live in the museum with her husband and baby, her work becoming the artwork; she would conduct a series of interviews with maintenance workers about things like “the relationship between maintenance and freedom”; and finally, she would process waste within the galleries of the museum. “CARE” would be repeatedly rejected by various institutions, but the proposal nevertheless shaped the rest of Ukeles’ artistic career.

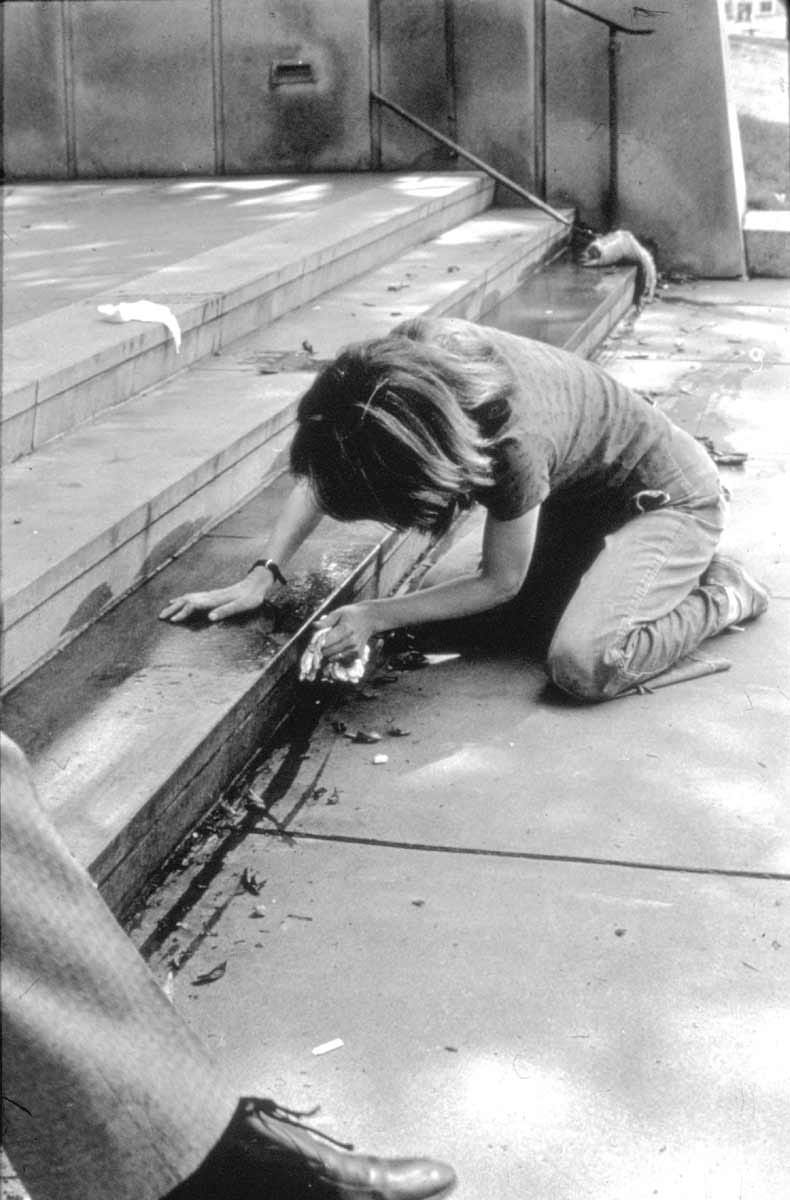

In a 1973 performance, for instance, Ukeles highlighted the maintenance work that allows the art world to function during a performance in which she scrubbed and mopped the steps of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum.

Ukeles penned her manifesto one year after becoming a mother, feeling like she was being pushed out of the art world. Ukeles said she wrote the manifesto “in a cold fury,” frustrated by the American avant-garde, which she felt was creating artwork that replicated industrialist processes and the unquenchable capitalist thirst to “make something new, always move forward.” Meanwhile, as Ukeles put it, “The people who were taking care and keeping the wheels of society turning were mute.” The manifesto emerged as a response to her sense of being “divided in two” by motherhood. “I am this maintenance worker, I am this artist,” she wrote. “Half of my week I was the mother, and the other half the artist.”

Ukeles’ recognized that the labors performed in the home were connected to other forms of undervalued maintenance work. As artist in residence for New York City’s Department of Sanitation (a position for which she was not paid), Ukeles worked closely with “sanmen,” whose work remains largely unseen in our daily lives. For her 1979 “Touch Sanitation Performance,” Ukeles spent 11 months interviewing sanmen and lecturing around the city on the value of their under-recognized, indispensable labor.

In this sense, Ukeles concept of “maintenance work” is a second-wave feminist precursor to the concept of essential work. In her manifesto, Ukeles writes that while most art-work emerges from the “Death instinct” of production – rooted in a desire for “separation, individuality” – maintenance work is concerned with “survival systems and operations” – “keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance.” Throughout her career, Ukeles questioned what subjects are deemed worthy of artistic representation and reverence, making visible the processes and activities that preserve human life.

Essential work, as we understand it today, has a more flexible definition, if only because it’s defined by whatever policymakers deem worthy of profit/value/policy. Essential work is supposed to be those nonnegotiable sectors of the economy we can’t live without. Though heavily sentimentalized by corporate marketing campaigns, essential work has more often been defined by the imaginary structures of economic markets and the unequal distribution of risk. This has given rise to numerous criticisms. Many of the positions that fell under the rubric of “essential critical infrastructure workers” as defined by US Homeland Security, for instance, were those worked predominantly by the poor or economically precarious and by people of color.

Essential workers are often maintenance workers, but the category has also been informed by lobbying power, by the effort to produce an illusion of normalcy (see: reopenings of bars and restaurants v. schools), and by other economic interests. Meanwhile mothers – despite being pushed out of the workforce to take on homeschooling, full-time caregiving duties, quarantine maintenance, and so on – remain the unacknowledged essential workers of the pandemic, as this episode of The Double Shift addresses (co-host Angela Garbes is literally writing the book on essential labor, and you can hear her talking in this episode about motherhood as a labor struggle.)

Ukeles defined maintenance work, on the other hand, not according to market forces, but as life-sustaining work. Maintenance work is, therefore, according to Ukeles, often repetitive, mundane, cyclical. She writes: “Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time (lit.) The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom.”

And it’s un/undercompensated: “The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewives = no pay.”

Maintenance work is what Marx referred to as social reproduction or what feminist socialists call reproductive labor. It’s care as infrastructure. It includes housework and caregiving, but also socialization and informal education. It’s the labor we all must do to maintain ourselves as individuals and as a species. It’s caring for the body, mind, self, for the children, for the elders, for the home, for anyone who is ill or can’t help themselves.

It also includes cleaning, processing waste, processing feelings, basic self-care, the kind of stuff we forget to do when we experience burnout (i.e. all the things I have let fall apart around me while I spent way too much time writing this post). Perhaps we notice maintenance work most when we have no time for it: when the body or the home or the family begin to unravel.

Maintenance work is material, physical, affective, emotional, psychological, immaterial. It’s made up of regenerative bodily acts but also domestic and personal upkeep. It’s all the work we’re not paid for that we nevertheless must perform for survival – and to reproduce ourselves for another day of paid work outside the home. It is what we have in mind when we say that capitalism is built on unpaid women’s work and on care work more broadly.

In our current age, in which the ideal worker is always on and wellness is a means to greater productivity and career advancement, maintenance work is also often privatized. We pay to optimize the body with wellness and fitness and bullet journals and productivity porn and other life hacks. We train ourselves into new habits. (The importance of maintenance labor to waged work is made especially obvious by corporate wellness programs and productivity seminars.)

Without maintenance work, we couldn’t show up as our best selves, or as any selves, ready to participate in a shared public life. We couldn’t have nice things or make any things at all. We couldn’t have the good life. We couldn’t have human labor power. We couldn’t have production. Maintenance, in this sense, is the most vital work we perform. And yet, it’s often rendered invisible. Until now!

We’re in a special kind of cultural moment, aren’t we? Women have been pushed out of the workforce en masse and other workers are leaving their jobs in droves. Birth rates are declining, because who wants to be a parent if one has to subscribe to American parenthood; employment in healthcare is down; no one wants to pick up your trash. Those who are already parents are growing more furious by the day about the unequal and gendered distribution of labor in the home, America’s horrible maternal healthcare, our lack of postpartum support and the recent gutting of paid leave. Childcare crises abound. The public hustle has lost its sparkle. Everyone hates going to work.

These are not new feelings and they’re all connected. Academics, political theorists, and cultural critics have been talking about the broader crisis of work for years. Social reproduction was also in crisis long before the pandemic, as maintenance work became increasingly privatized for those with means to contract out the work and further burdened individuals who couldn’t afford to pay for help.

Nancy Fraser has argued that capitalism has a crisis tendency, and central to this crisis vibe is the never-ending redistricting individuals must do: we debate what counts as economy vs. society, work vs. family/“life”, production vs. reproduction. The utter precarity of everything layered on top of the utter precarity of an ongoing pandemic that has been handled terribly only makes things worse.

But what if we valued the collective, life-sustaining practices we all must conduct to perpetuate ourselves and our communities? What if we valued everyday reproductive labor for what it is – truly essential work?

Fraser notes in Fortunes of Feminism that in America we follow a Universal Breadwinner model, which relies on the assumption that masculine forms of work are the ideal to which we all aspire. Caregivers are expected to support themselves through waged work outside the home (or on Zoom), while childcare and elder care are contracted out either to the government or private care centers. For this model to succeed for more than just white men (which obviously it is not currently doing), strong policy supports in the form of “employment-enabling services” have to be in place. This means things like paid leave, universal pre-k, affordable child care that doesn’t send care workers into poverty or rely on poor and immigrant labor, workplace reforms to change cultures of gender inequality, and more. Without such supports, women will continue to be forced to take the hit and do the maintenance work for free.

Western European feminists and social democrats, Fraser writes, favor another model. Caregiver Parity supports informal, domestic care work either through compensation on par with work outside the home and/or policies that relieve the stigma women experience when splitting part-time work in the home and part-time work outside the home. This model would raise care work to the level of waged work. In contrast to the Universal Breadwinner model, Caregiver Parity does not aim to make women’s lives look more like men’s lives, but rather seeks to recognize care work as “intrinsically valuable.” Policies like paid leave, mandated flex time, professional retraining and reentry programs for those whose care work necessitates career shifts, continuous social services such as unemployment and healthcare, and other things we don’t have in the U.S. – all are crucial to the success of this model. But Caregiver Parity also runs the risk of further feminizing care work and therefore failing to achieve comprehensive gender justice.

A third possibility, Fraser writes, is to “induce men to become more like women are now – viz. people who do more primary carework.” Feel your heart pitter patter and leap from your chest! After all, as Fraser points out, the real abusers of our current systems are not single mothers on welfare, but men who don’t contribute their fair share to care work and domestic labor, feigning and weaponizing their own incompetence, along with corporations, who rely on workers’ unpaid maintenance labor to reproduce and enhance their labor force.

Fraser calls this idea of inviting men into the fold the Universal Caregiver model. It’s similar, in some senses, to what’s been proposed by popular feminist thinkers like Eve Rodsky in her book Fair Play, which offers systematic solutions for balancing domestic and caregiving work between parents. For the Universal Caregiver model to succeed, however, gender relations in the nuclear family, its own private institution, are not all that would have to shift (as Rodsky understands). The model requires centering maintenance labor’s collective value above and beyond the self and the family – a re-imagining of work and family life. Rather than divide work into tracks (domestic vs. public), everyone would have access to employment-enabling services and policies that see care work as valuable. Citizens without “kin-based responsibilities” would also join in on communal care work.

Real gender equity in the workforce, in other words, requires dismantling the concept of gender and what Fraser calls the “gender-coding” of care. The struggle to liberate ourselves from gendered expectations and the struggle against work are deeply linked. Both require that we upset the hierarchy between maintenance work and other forms of work. As Fraser writes, “The trick is to imagine a social world in which citizens’ lives integrate wage-earning, caregiving, community activism, political participation, and involvement in the associational life of civil society— while also leaving time for some fun.”

Though American parents, and mothers in particular, have struggled with lockdowns and quarantines, many Americans (including those who struggled!) have also been reconnecting with maintenance work. Sometimes, this has taken the form of cringey privileged homesteading or consumerist, individualistic cozycore cries for help. But we have also learned to see more clearly the unsustainable, frenetic, all-consuming pace of American work in which we were all previously stuck. No one wants to go back. We’re experiencing a collective disillusionment with waged work. We had a taste of life more focused on maintenance and some of us want more.

Some maintenance work in which I learned to find pleasure during the pandemic: baking bread, although that lost its appeal fast; caring for my body, learning to recognize that I have feelings and buried trauma that needed tending, caring for my children’s bodies, long runs and walks, sleeping in.

Not all maintenance, though, is pleasurable.

Some types of maintenance work I came to detest: all of the manufactured maintenance tasks that filled in the failure of public policy, such as sitting on the phone for hours with EDD or the bank or insurance companies; nagging my daughter about virtual kindergarten or my son about playing by himself while I tried to work; processing and managing my own affective horror and rage. I disliked the domestic tasks, too, the endless housework, including picking up the living room several times a day and cooking three meals for the children plus snacks; the never-ending laundry and dishes and mess.

I have worked as a nanny and at an in-home daycare, jobs where all I did was perform various forms of maintenance labor. Cooking, cleaning, caring. Those jobs have no doubt colored my experience and my read of maintenance work. Some forms of maintenance work really are a drag. And yet, so much of what we gripe about when it comes to American care work has nothing to do with the work itself. I have said this before: though care work is inherently trying and sticky and creative and laborious, I refuse to believe it’s the work of raising children that’s so tedious and painful and tragic. What makes American parenthood so intolerable is the forced isolation, the loneliness, the gendered imbalance of work, the exploitation, the devaluation, the go-it-alone-ness. The real drag is how little we value maintenance work.

I am an extremely introverted, solitary kind of person, but I still fantasize about what dish-doing and laundry-folding and child-watching and cooking would be like if it were performed in a community. I get a taste of it sometimes. At family gatherings, when the kids play together and the adults are free to gossip and chat, but also, by turns, talk and laugh with the kids, who are odd and vexing, but also utterly delightful. When my children spill into the street to play with neighbors of all ages for hours. When I get a little break from work and fast-paced caregiving and I feel my nervous system resetting and my arms spread out wide to envelop and breathe in my children, my urge to hold them animal and desirous. Before I reenter the everyday and the system revenges me for daring to just be, I feel the pleasure of maintenance.

I don’t always like maintenance work. But I do think I would like it better if I had more time for it, if others recognized the creative, artistic quality of the work. To imagine this future, however, we have to continue asking the question Ukeles posed in her manifesto, which feels like it has new relevance today: “after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?”

Want to purchase a gift subscription for a fellow mad mom? For just $5 a month or $50 per year, you can give the angry mama or anti-gender caregiver in your life the gift of analysis and community.

Paid subscribers receive access to all posts, along with a monthly writing prompt designed for those of us trying to carve out a creative life between all the other work we do. Paid subscribers can also share and discuss their writing with a supportive group.

Or, gift yourself a subscription.

And: every time you share a post, a newsletter gets its wings.

Incredible piece. Thank you.