The Fear of Caring Too Much

If mothers are still to blame for everything, why can't we afford to support them?

To get into the Halloween mood, over the weekend Jon and I watched Pyscho. For those in need of a refresher, the film begins with Marion Crane, an independent working woman, running away from her oppressive life working as an assistant in a real estate office. When she gets caught driving in heavy rain, she is forced to pull off on a strange road and the film is overcome by that special, spooky tension that can only be created by the ever-looming potential of male violence. Marion has also stolen $40k from her boss, making her not just a vulnerable woman, but also one running from the law. At the motel, Marion meets the boyish Norman Bates, who invites her to the big house on the property for sandwiches and milk. But then he has a loud fight with his controlling mother who doesn’t want him getting all lusty with Marion, so Norman creepily watches Marion consume her sandwich down in the hotel office. As they chat, he reveals the central horror at play in the film: "A boy’s best friend is his mother," he says.

Spoiler: mother is long dead. Throughout the film, however, she is characterized as a madwoman in the attic, possessive, and domineering. Eventually it’s revealed that mother lives only in Norman’s psyche – you know, as mothers do. This internalized mother figure forces Norman to kill any woman who arouses him, seeing other women as a threat to Norman and mom’s perverse mother-son love. Though Norman remarks that “a son is a poor substitute for a lover," their mutual codependency haunts the film. When Marion asks why Norman doesn’t just have his mother committed, he snaps, "What do you know about caring?"

Indeed, Norman, what do any of us know about caring? "She just goes a little mad sometimes,” Norman says in a well-known line. “We all go a little mad sometimes."

One nearly sympathizes with Norman, the doting caregiver of a sick, demented old lady. After the sandwiches, though, Norman watches Marion undress in her motel room through a hole in the wall. In her iconic essay on the male gaze, Laura Mulvey notes that many of Hitchcock’s films render women passive victims of male sadism and voyeurism. But poor Marion thinks she is alone, so she takes a comically sexual shower, extending the scopophilia for filmgoers, and, well, you know what happens next. Norman kills Marion in the famed shower scene, then blames his mother – as killers do.

At the risk of upsetting every (male) film student, the shower scene feels, decades later… unremarkable. But the film’s narrative – which renders a mother’s love always dangerously close to madness – feels pretty timeless.

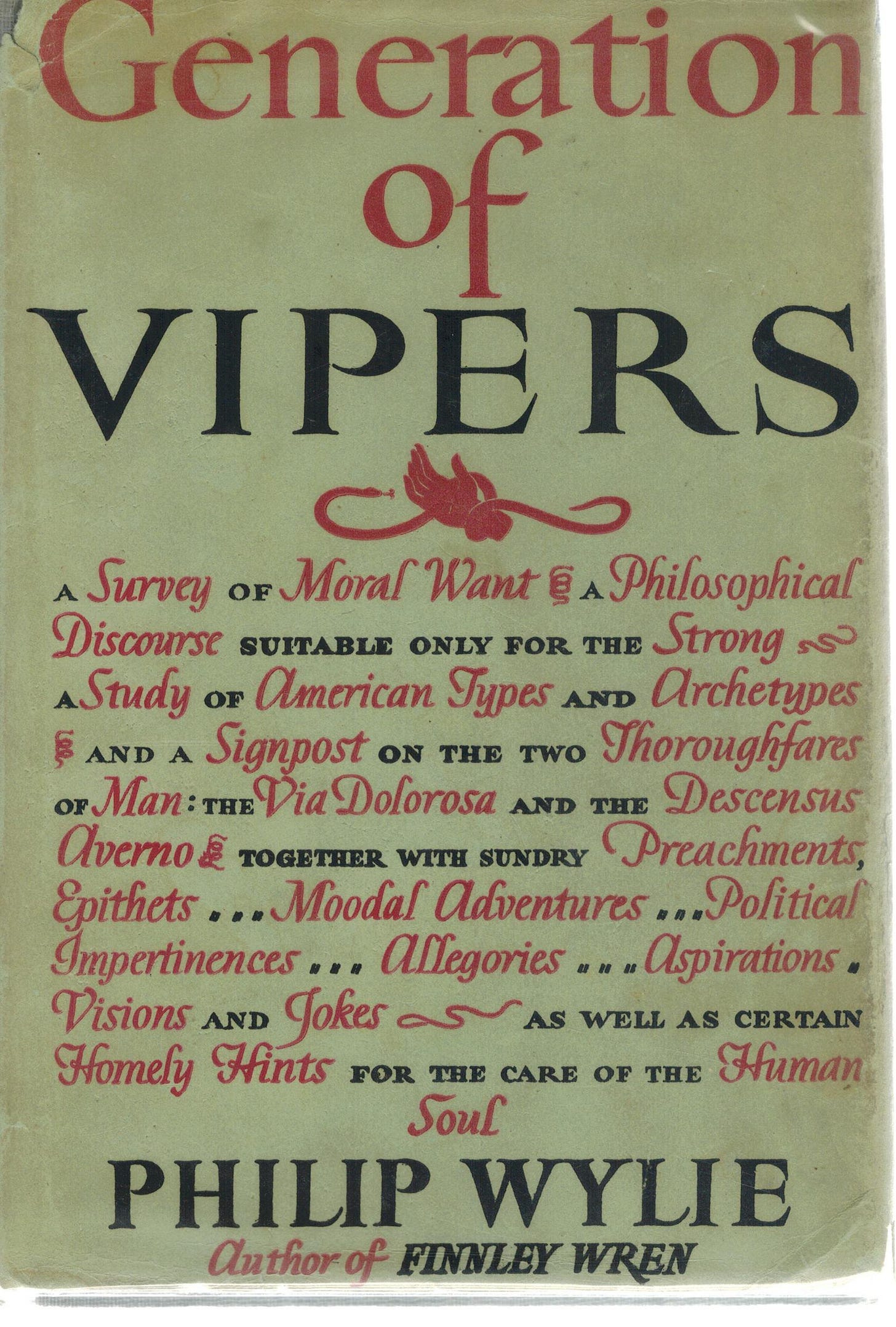

Representations of maternal love often reflect national ideology. Because parenting is a political dialectic, there are plenty of symbolic prohibitions that check the power of those who raise us. When Psycho was released in 1960, Americans already held a deep skepticism of women who loved their children too much. Freudian incest fears had spread to popular culture. In 1943, in his best-selling book Generation of Vipers, Philip Wylie blamed “megaloid momworship” for numerous forms national suffering, including the widespread PTSD experienced by those returned from the war.

Wylie also blamed smothering mothers for casualties of war and for the psychological ailments of men who didn’t qualify for military service. Wylie’s theory of “momism” was deeply rooted in homophobic logic, characterizing over-attached sons as weak and psychologically compromised. His writing was, confusingly, both anti-free enterprise and anti-Communism. But Wylie’s distrust of maternal desire outlasted the book’s momentary popularity. In the 1946 book Their Mothers’ Sons, Edward Strecker drew on Wylie’s writing, issuing a finger-wagging to overbearing mothers who had failed to wean their sons emotionally, preventing them from becoming a “man, in the truest sense of the word.” As one reviewer put it, Strecker’s project explored how the “Great American Mom” emasculated her sons, creating “soft spots which made them incapable of independent, mature action in the face of even minimal difficulties.”

In a 1946 piece for the Saturday Evening Post titled “What’s Wrong With American Mothers?”, Strecker listed a number of psychological conditions experienced by those wounded by the masculine violence of war – including combat fatigue and “dozens of other mysterious complaints” – tracing them all to the “parental failing” of mothers who found too much “emotional satisfaction” in their work. The problem with moms, Strecker argued, was their inability to “sever the emotional apron strings” and teach their children the “maturity” required for wartime. “No nation is in greater danger of failing to solve the mother-child dilemma that ours,” Strecker wrote, “and no nation would have to pay as great a penalty as the United States for not solving it.”

Variations on this theme persist today. Helicopter Moms, theories of overprotection, mom-as-meddler, mama’s boys, Matthew McConaughey’s pathetic role as Tripp in Failure to Launch—all are reverberations of momism. Paradoxically, both “intensive parenting” and resilience culture also draw on this history. Contemporary parenting philosophy and attachment science are rabbit holes I will save for another post, but what’s familiar about both discourses – those on over-parenting and under-parenting – is that mothers are still often framed as a direct threat to their child’s ability to flourish as an independent agent in a highly individualistic culture. Which is to say, mothers are still to blame for everything. What has recently begun to set some contemporary conversations about parenting apart is the recognition of what “momism” missed, which is that caregiving approaches are shaped by parents’ socioeconomic status and working conditions – themselves shaped by public policy.

Second wave feminist writing on motherhood also often targeted moms, rather than the context in which they worked. White, middle-class feminists frequently blasted their mothers, as well as women of their own generation, for their decisions to take on maternal roles and to in turn remain complicit in their own oppression. Betty Friedan, for instance, writing for that white, middle-class audience of women in 1963, identified in The Feminine Mystique two types of mothers: those who viewed motherhood and homemaking as so central to their identities they had “worn out six copies of Dr. Spock’s baby-care book in seven years,” and those for whom motherhood remained that troubling “problem with no name.” Friedan often described motherhood as a source of either fraught pain or ignorant pleasure, taking issue not only with the institution of motherhood, but with the women who found gratification in domestic and maternal labor. She also argued that women who doted excessively on their sons turned them into homosexuals.

Black feminists like bell hooks have pointed out that had their voices been more central to the second wave conversation, work outside the home would not have been named a primary indicator of freedom, since Black women had always worked outside the home. But the dualistic vision that appears in Friedan’s landmark book has been hard to shake, in part because, economically and therefore culturally, we still do not value work performed inside the home. In the early aughts, that vision morphed into the SAHM/working mom “mommy wars.” And Koa Beck documents in her book White Feminism how neoliberal corporate feminism continues to center the movement around a wanting of what men have, even as work outside the home, as we currently understand it, is completely failing us. At the heart of this ongoing bifurcation in the feminist movement is the question of whether aspiring to masculine, capitalist, colonialist models of work can be feminist at all – but also the reality that many often feel there is no alternative to which we might aspire.

Meanwhile, American policymakers consistently make it painfully clear that a world in which work works for all of us isn’t really something they are ready for. Last week, the news dropped that the 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave initially proposed in Biden’s Build Back Better Act was likely to be gutted or axed. (At the time of writing, Nancy Pelosi is saying she wants to keep 4 weeks of leave.) Joe Manchin has griped about several elements of paid leave, saying he’s concerned about “an awful lot of things” and that the program “doesn’t make sense” to him. He also reportedly expressed concerns about the program’s work requirement, but as many have remarked, such comments just betray his own ignorance about how paid leave works (and therefore his own failure to fulfill the duties of his work). Advocates of paid leave have rushed in to remind Americans that in 186 other countries paid leave is doing just fine.

Conservative policymakers routinely invoke their concerns about cost in their resistance to social services. “I want to work with everyone as long as we can start paying for things,” Manchin said. “That's all. I can't put this burden on my grandchildren.” As if he’s being so reasonable! But there is plenty of money to go around (especially for his grandchildren) and numerous studies validate the economic, social, and cultural benefits of paid leave. Manchin’s excuses, and the handwringing of all those Republicans, are just diversions. They rest on the idea that investing in care is so precarious, so dangerous, so on the brink of insanity, it can hardly be trusted to work in our collective favor.

What if mothers become too powerful? What if they smother us? What if they don’t like us anymore? What if they destroy everything? What if they break our hearts? What if caring, taken to the extreme, looks like death?

Perhaps some of this fear is not entirely unfounded. Investing in care is a radical notion. Done right, such investments could destabilize the inequality that is inherent to many of our most integral assumptions about the family and work. That’s precisely the point. Centering reproductive labor and care work on a national scale requires that we explore some of our deepest fears about what we collectively value, whose concerns matters most in this country, and why.

After Marion’s death, her sister and lover seek out help from a local sheriff. Like American lawmakers, the sheriff is totally distracted by the money situation – that $40k Marion stole from her boss – and is generally horrible at his job. He calls Norman and takes his word that he knows nothing, even though Norman is a terrible liar AND the sheriff knows that Bates’ mother and second husband were poisoned to death a decade ago while Norman was in the house! (That crime was blamed on Norman’s mother, too.) So, Marion’s sister and lover do some digging at the Bates Motel on their own. Marion's sister sneaks into the big house where she finds Norman’s mother in the basement, only to find that Norman’s mother is nothing but a skeleton, dressed up in elderly woman’s clothes. In rushes Norman, also dressed as his mother, with a knife, yelling, “I'm Norma Bates!”

Like many canonical horror films, the end of Psycho codifies transphobic myths and generally does not age well. It also speaks to a deeply rooted cultural anxiety that is very much alive in America today, one that revolves around what might happen if we were to acknowledge, collectively, that the line between child and mother – between self and other – is incredibly thin.

In the final scene of the film, a male psychiatrist analyzes Norman, mansplaining the hidden elements of the plot to the audience. Norman’s mother was "a clinging demanding woman." Norman killed her because of his disturbed lust – a pathology for which, yet again, Norman’s mother alone is held responsible. Horrified by his own matricide, Norman “became” his mother to cope. It’s a tortuously confusing, hodge-podge, problematic diagnosis. In The Women Who Knew Too Much, Tania Modleski attributes the confusing place of women in Hitchcock’s films to his own ambivalent (and at times misogynistic) feelings about femininity. Perhaps this is why, as I watched the film over the weekend, even though it felt dated, so many of the cultural anxieties under the surface felt resonant and recognizable.

The story of a monstrous man driven mad by his fear that he will be swallowed by his mother, by love – that he’ll never be a real man if he cares too much. A man who instead pursues power by harming other women, those who come to him for shelter. A man who represents the fear so many men seem to carry – men who blame their mothers for their own shortcomings, while failing to support those who rear and raise us. What could be more terrifying?

Some recs:

Men not participating in the labor of child rearing is terrifying and Meg Conley always writes with such empathy and intellect. She’s also one of the few writers I know of who continuously underlines how capitalism leans on unpaid care work. Check out her piece on fathers making time to care.

Lydia Kiesling has a poignant piece at The Baffler about navigating the postpartum body, EDD, and blood on the floor.

Angela Garbes and Katherine Goldstein are running a series at The Double Shift on mothers as essential workers.

Check out Paid Leave US to help out or donate.

This kind of reminds me of post partum depression. Even though men are just as likely to rage kill their child, it was me who wondered every time I felt desperate if I was the next Andrea Yates (whose husband unbelievably bore no responsibility for her children's deaths). Every post partum visit and its question "are you thinking about hurting the baby?" had me wondering when the killer deep inside me would appear. My husband, however, has never once been asked this question even though, statistically, he's at least an equal threat if not greater.