The controlled sexuality of American cheer

Purity culture meets sex work meets aspirational womanhood meets endless girlhood

If the first season of Netflix’s America's Sweethearts: Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders felt like a tepid expose, this season feels more like a nationalist sentimentalization of American cheer, streaming on Netflix at the worst possible moment. The show even opens with a montage of the DCC’s strict rules and the faces of the women trying to shake up the organization’s “girl next door” image, set to Tom Petty’s “American Girl.”

The song is actually the perfect scene setter for a series that feels less like an illuminating docuseries about an American institution, and more aligned with the recent conservative women’s conference hosted by Charlie Kirk’s Turning Point USA— also held in Dallas earlier this month. Perhaps you have heard about this abomination of a “leadership summit,” during which Kirk explicitly remarked that success for the MAGA right looks like women staying home? “We should bring back the celebration of the Mrs. degree,” he said.

Well, at least he’s being frank about it. It’s much harder to pinpoint the politics of the DCC, though the team mentality does reek of purity culture and traditional feminine roles. DCC husbands are a whole thing, and while some women insist that getting married and having babies isn’t the only next step for DCC cheerleaders, it’s clear based on the existence of such a conversation that for many, that’s the expected path.

On this season of the Netflix show, one of the most pious DCC members featured discusses how her husband mostly takes care of her, rather than the other way around, because of her nonstop schedule. These are women, in other words, with uncompromising professional ambition, but even to themselves, its not always clear what they are hoping to gain beyond a multi-year stint on the team.

The DC organization has a clearer politics. Jerry and Charlotte Jones, who own the Dallas Cowboys football and cheer teams respectively, reportedly have million-dollar ties to Trump. There has been, to my knowledge, only one openly gay DCC cheerleader and no trans members on the team. The entire aesthetic of the team is also rooted in white, fatphobic beauty norms.

The show, as a result, oscillates indecisively between celebrating the spectacle of femininity that the DCC represents as iconic Americana (with absolutely no acknowledgement of how that plays off, say, nationalism), and noncommittally covering the labor demands of the team, as veteran cheerleaders demand a raise.

Sometimes, the labor politics get interesting on the show, such as when we get to see how some women are taught to devalue their own worth, while at the same time reaching for trad feminine qualities like sacrifice, submission, and kindness to prove they are worthy and good. We also get a glimpse at how other women rationalize poor their labor conditions.

One team member, for instance, who works at a DCC summer camp, admits the women slept in dog beds in the locker room (!) because they were given so little off time between events and rehearsals. Two newer cheerleaders defend their low pay, explaining that, well, they just do part-time work anyway. When pressed with the question of how many hours they work each week, the women admit it’s about 40 hours. But, it’s seasonal, they say, only eight months out of the year. Meanwhile, the show highlights the all-consuming training that takes place outside that 8-month season, just to get a spot on the team.

More troubling, the DCC higher-ups appear to ice out several women involved in contract negotiations, and at one point, the team even gives up their plans for a walkout under pressure. The women did finally get a significant raise from the Cowboys franchise, itself valued at over $10 billiion. It’s unclear how much the cheerleaders will make moving forward, but some estimates have the number at about $150,000 per year for the most veteran team members. Sounds good to me! But for comparison, in 2024, Dallas Cowboys players— ehem the men— were paid $796,000-$60 million.

The ethos of DCC, however, is very do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life. But many women on the show question what it’s all for, and whether being on the team is worth the emotional and physical toll (some decide it’s not). They also witness the popularity of the team rising, after the first season of the Netflix show, and question why they are still so undervalued within the DC organization.

These labor politics are not deeply or meaningfully explored on the show, nor are the inseparable gender politics. But I couldn’t help but notice that the DCC, as an American insitition, says a lot, all on its own, about the economy of women’s sexuality today. In many ways, the DCC’s aesthetics and labor practices embody the values of the new American right.

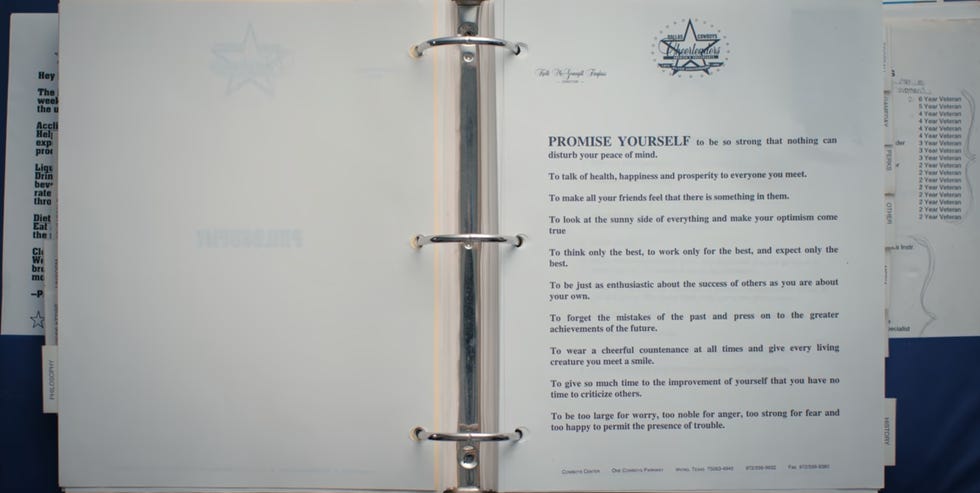

The women are, after all, not just dancers, entertainers, but sexual consumables within a highly masculine athletic arena. The women wear shorts that are so short, they barely register as shorts; they sport heavy cleavage. More to the point, Cosmo recently published 23 rules the DCC has to follow, including maintaining weight and diet, not dating players, wearing full hair and makeup, no worrying or feel anger (!), no pouting or whining, responding “yes ma’am,” and wearing “a cheerful countenance at all times” (!!).

Many have traced the roots of the DCC, however, to a woman who bucked traditional femininity. Bubbles Cash, a dancer who worked at a local burlesque club, caused a stir in 1967 when she attended a Cowboys game carrying two cotton candies in front of her breasts and the crowd lost it. Soon, other women were showing up at the games, rushing the field to kiss players and coaches. In 1972, the Dallas Cowboys saw an opportunity to monetize the spontaneous, subversive sexuality that had erupted.

Years later, the brand of feminine sexuality represented by the DCC “girls” (they are women) is both excessive and tightly controlled. One woman was kicked off the team in 2021 for being too provocative online. There are extremely fine borders, in other words, around the sexuality inherent to the brand. The women are expected to be model citizens, and many have experience in pageant culture, which itself sexualizes and objectifies young girls and women, but also becomes a stage through which contestants renegotiate questions about gender, race, power, and body politics.

And it’s that kind of at-odds negotiation that makes the DCC reality shows so enticing. The women’s sexuality perfectly blends a girly, slightly pedophilic, white hypersexuality, which fits pretty comfortably today inside a conservative politics that permits some women the illusion of public power— so long as that power does not swerve outside the interests of the institution, which not only puts men literally at the center of the production, but also at the economic table.

The DCC’s distinct dance style feeds the tension. Their dances are referred to by members of the team and by higher ups as “powerful,” but one rookie candidate calls their vibe “sassy, sexy, happy,” and points out that it’s a far cry from the more aggressive, muscular dance team she belonged to before DCC.

Still, as Sarah Hepola, host of the podcast America’s Girls, noted in an interview with Emily Leibert, Dallas is heavily influenced by Baptist ideas of sexual purity, which does make the DCC’s blatant sex appeal subversive. The kick line is a signature feature of the DCC show (as are those painful-looking jump splits, known to cause hip injuries), and while it would be easy to toss all these leg splits off as purely for the male gaze, the history of the kick line is more complicated, with roots in drag, the Can-Can, and gender transgression.

As Lauren Elkin writes of the chorus girl, “The gaze that falls on her is sometimes male, sometimes female, sometimes singular, sometimes multiple.” She is as much a saleswoman of the franchise, as she is “selling a dream” of womanhood rooted in girlhood— that is, a fantasy of who little girls might become, but also, for older women, of endless youth.

I think it’s the lure of these shows, watching the women navigate the maintenance of their own purity, their gender performance, and their belonging within a what amounts to a pretty militant, strict culture that at once respects what the women can offer the brand, and devalues what they can offer the world.

But there’s an incredible and disturbing dissonance between this highly gendered spectacle and the aggressive attacks on women’s rights in America today. The DCC, branded as “America’s sweethearts,” subscribes to an incoherent, neoliberal “feminism” of ambition and representation. Representation matters, the Netflix show seems to argue, spotlighting Black and biracial cheerleaders shifting the standards of beauty on the team. But whatever each member’s personal poltics may be, DCC members seem to be discouraged to talk about them explicitly in public. And so the DCC’s neutral, nationalist politics of representation sits uncomfortably against the backdrop of the overt racist and misogynist violence against women happening in America today.

And the organization isn’t exactly immune to a culture of gender inequality. The DCC has struggled to confine the cheerleaders’ sexuality to the team, but it has also been plagued throughout its history by accusations of sexual harassment, as has the rest of the sport. In 2018, a Times report found that Washington Redskins cheerleaders had their passports taken from them on a trip to Costa Rica. Then, spectators were invited to watch them pose topless for a calendar photo shoot. Later, some cheerleaders were told they had to serve as escorts for male donors. The cheerleaders said they felt the team was “pimping” them out.

Today, American cheer’s tightly controlled embrace of women’s sexuality reflects the wider political moment in which we find ourselves. Once a woman is perceived to be using her sexuality for her own gain, she is viewed as having resigned all access to consent and basic human dignity— to being forced to use her sexuality for others’ nefarious purposes. Should she try to use her sexuality for her own gain outside the approved economic structure, she is perceived as a threat to our entire moral, social, and economic fabric.

Meanwhile, late capitalism continues to run on women’s work, and on women’s images. Today, women are not just sexual objects, products for male consumption; they have become economic and political sidekicks— who better not let that uniform get to their head. They can stay, as long as they behave.

In the second episode of this season of America’s Sweethearts, the “girls” all undergo written testing to show they are “more than face and figure.” But their education, we soon find out, is limited to Cowboys trivia. It’s a reminder that, right now, for many in America, women are only more than their face and figure when they are training to be adjuncts of men.

This is an interesting article. You are right it is a highly controlled form of dance. I took dance classes as a kid (I still dance ballet), and did a few "cheer" classes now and then when they brought in a guest teacher but they were super boring. IN cheer-leading there are a few basic arm movements (buckets or candlestick) and kicks and jumps that are just repeated over and over in different combinations. There's not much musicality and limited emotions that can be expressed. Us dancers looked down on the cheerleaders in our school since the moves were so basic, and lacked any sort of innovation or artistry. Their routines were clearly sexualized to entertain the audience. I feel bad for them because I think they really thought they were cool or good dancers.

I saw a documentary on the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders a while back, and it was brutal, so much body shaming, relentless dieting, eating disorders, practicing, they even went into war zones to perform for military troops and had a few close calls.

Interestingly, cheerleading was historically male-dominated, especially at the college level (they didn't really let women int back then) President Bush II was a cheerleader in college at Yale. Reagan, Eisenhower, and FDR were also cheerleaders too apparently.