It’s getting increasingly hard for me to avoid beginning everything I write to you with some acknowledgement that the world is falling apart around us. This morning I re-read my heavily annotated copy of Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, and so, I’m sharing my reflections on what I found, and what I’m thinking about, below.

In her analysis of how we respond to images of war, Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag writes:

Who believes today that war can be abolished? No one, not even pacifists. We hope only (so far in vain) to stop genocide and to bring to justice those commit gross violations of the laws of war… and to be able to stop specific wars by imposing negotiated alternatives to armed conflict.

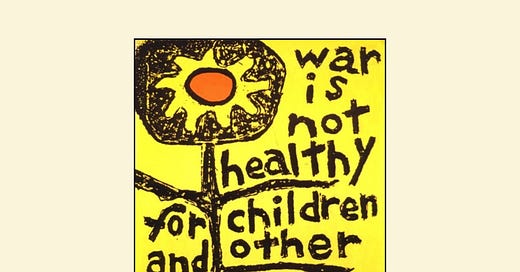

When I read this passage now, I’m struck with both recognition and anger. I nod my head— not enough people believe, truly, in the abolition of war— and I also want to yell at Sontag— I believe! I want to insist that this kind of hopelessness is not true of this era, when it seems, at least in my echo chamber, that many in America are more patently opposed to war than I can recall in my lifetime.

But Sontag’s point is not the inevitability of the hopelessness, or, really, of war. In an interview about Regarding the Pain of Others, she said that the book “really wants to talk about how horrible war is. Precisely in the way that images both convey it and can’t convey it.” She continues:

What I want people to think about is how serious war is. How it is elective. It’s not an inevitable state of affairs. War is not the weather. I want people to think about what war is. And at the same time, I know it’s very hard. I end the book by saying, in a way the world is divided into people who know— have had direct experience of war, and people who haven't.

And if you've had a direct experience of war [then you know] it is both more horrible than any kind of pictures could convey, and maybe one of the most horrible parts of it is that it becomes a normality. It becomes a world that you can live in. There is a culture of war.

In the book, she recalls the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, also referred to as The Pact of Paris, which condemned “war as an instrument of national policy.” It was signed by the US, among other nations. What happened to that?

Sontag notes that the pact led to a public letter exchange between Freud and Einstein titled “Why War?” I looked up some of their arguments. Freud’s premises are Lockean and naturalizing. He argues that war is just part of human nature, and the best we can do is find ways to restrain male aggression. The following passage of Freud’s makes me want to throw my computer across the room:

Conflicts of interest between man and man are resolved, in principle, by recourse to violence. It is the same in the animal kingdom, from which man cannot claim exclusion; nevertheless men are also prone to conflicts of opinion, touching, on occasion, the loftiest peaks of abstract thought, which seem to call for settlement by quite another method. This refinement is, however, a late development.

To start with, brute force was the factor which, in small communities, decided points of ownership and the question of which man's will was to prevail. Very soon physical force was implemented, then replaced, by the use of various adjuncts; he proved the victor whose weapon was the better, or handled the more skillfully.

Einstein wrote that “a change could be brought about by a free association of men whose previous work and achievements offer a guarantee of their ability and integrity”— in other words, what was needed was an intellectual elite, an international council, not unlike the UN (not created until 1945, after the horrors of WWII) to keep the peace. But he also admitted that this would mean every country would have to surrender its own nationalism, and didn’t think that too likely.

Einstein at least wrestled with political questions about how minority ruling classes can weaponize the church, press, and education, stirring enthusiasm for war from the masses, who might otherwise resist war, because they are the ones likely to be most affected by it. But his conclusion is largely the same as Freud’s: humans have an instinct for violence.

Sontag’s book is in large part a response to Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas, which was itself published later, in 1938, as a response to these ongoing conversations about how to prevent war. It was an unpopular book, and you can guess why: Woolf argued, in Sontag’s words, that “war is man’s game— that the killing machine has a gender, and it is male.”

This is what Freud and Einstein miss entirely. Not that men are inherently or instinctually violent because of their sex, but that there is a masculine quality to rage, aggression, domination, imperialism, conquest, retribution, and violence. That they are two white men failing to discuss gender and racial hierarchies as primary motivators for war.

In her timely summary of women’s objections to war,

wrote this week about Three Guineas:Woolf makes the point that political fascism starts with and stems from fascism in the home where brother is ranked above sister, husband above wife, father above mother.

Most of her treatise on how to prevent war centers on dismantling this patriarchal hierarchy. She says patriarchy and militarism are one in the same- to fight one we must fight the other. War is patriarchal by design. To end war, we must tackle patriarchy.

Sontag focuses less on what Woolf has to say about causes of war. Instead, Sontag’s subject, given her expertise in photography, is mostly on the images of war we consume, and whether they have the power to end war— a subject that has become increasingly relevant in the age of social media, when we are confronted daily with images of genocide and global conflict.

Sontag points out that Woolf “professes to believe that the shock of such pictures cannot fail to unite people of good will,” but Sontag asks with skepticism, throughout her own book, and just as we might ask today, “Does it?”

For Sontag, the issue at the heart of this question is that we cannot take any “we” who view the images of genocide and war for granted. The “we” may write off the picture, especially today, as mere fabrication, as fake news, or as confirmation of the atrocities of the other side, depending on who the viewer of the image is. Viewers will respond in such a way to validate what they already think, to confirm their own politics.

Maybe that’s an equally dismal view of human nature— that we cannot be moved in this age. But I am not saying such responses to images of carnage are justified, or even natural, just that it seems today that simply sharing or consuming images of violence will not automatically lead the viewer of such images reject that violence. That is, in Sontag’s words, “unless one thinks (as few people actually do think) that violence is always unjustifiable.”

I don’t believe violence or war or genocide are ever justifiable. We were simply born into a culture that long ago habituated to the idea that international violence is at times necessary. What we are witnessing now are more men’s wars, from which women and children suffer most.

But not all people believe this, and while it enrages me that they do not, Sontag’s point still makes sense to me. We have seen that photographic documentation of the violence of genocide and war is not enough for many to revisit their belief that untold, unprecedented violence against civilians is necessary in some cases—such as those who believe that countries have a right to defend themselves or that retribution is justified, or those who do not view the contradictions in American military policy as a form of imperialism, but rather as a well-deserved exceptionalism.

That said, I do think that the carnage we have witnessed over the past years in Gaza has shaken many into new beliefs—though certainly not all, not enough. Even those who have been moved, who are constantly moved, may find themselves dissociating, growing numb, struggling perhaps not to empathize or care, but to function in the dissonance and volume of our current moment— the constant onslaught of images and accounts of violence, at home and abroad, all taken next to one’s relative safety and the (albeit increasingly tenuous) surface-level peace in the US, does not necessarily alone create any more safety for those represented in the images.

“Being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country is a quintessential modern experience,” Sontag writes— but it is also a distinctly American and European experience, a white experience, which she fails to acknowledge. However, she did acknowledge that pictures of war are limiting in their ability to end war precisely because even as they “tell us how terrible war is” they don’t communicate why war is wrong— and they also confirm that we, in contrast, are safe.

While it may be true that images educate the privileged and the protected, Sontag insisted, this has to be taken alongside “the complacency and the fearfulness” of America, and how that contrasts with parts of the world where this conversation is totally irrelevant, because people see every day the terrible violence of war.

“For a long time,” Sontag writes in Regarding, “some people believed that if the horror could be made vivid enough, most people would finally take in the outrageousness, the insanity of war.” I’m not so sure I believe in the power of image anymore, and to be honest, I’m not sure what could move those who believe others should live with a firsthand knowledge of war, with constant fear and grief, with such a precarity of life.

But I still refuse to believe that this immovability is an experience that is inherent to human nature. The impulse to look, to feel, to care, to regard others who have been dehumanized as human as our neighbor, or child, and to struggle toward peace, that is still there in so many of us, it’s somewhere in that vague, inconsistent “we”— and that is human instinct, if there is such a thing.

https://open.substack.com/pub/thenoosphere/p/want-to-topple-the-patriarchy-learn?r=1r0idy&utm_medium=ios

Are we reading Katie Jgln’s work? Because I feel she does an excellent job of arguing that *humans* are not inherently violent, but these so called alpha males are the problem… a problem which is not an inevitability. This piece really gave me hope and totally demolishes the idea that the animal kingdom is an excuse for patriarchal dominance. There’s another path. We didn’t begin this way.