It feels like I have been seeing the word “ambition” everywhere. I see this word used by feminists discussing the state of mothers who want to work outside the home, in writing about well-known artists or writers, in conversations regarding how many women have been pushed out of the workforce. I cringe when I see this term—“ambition.” And I have been trying to figure out why.

My trouble is not with women (like me) who have desires to engage in a world beyond the home, beyond mothering, beyond domesticity. My trouble is with “ambition.” What do we mean by this? Why are we evoking this term so often now? Are we talking about the individual desire for success, status, money, fame, productivity, legacy, but just trying not to name it as such? Why aren’t more people problematizing this term?

It’s a semantic debate, perhaps. Lots of folks use this word in different ways. But it also seems like “ambition” has become a stand-in for a careerist mentality, a softer term for #bossin that still means placing work at the center of one’s value system.

I should note here that I am not exempt from locating my own value in my work. I tried not having “ambition” after I had my children. Though it would be more accurate to say that my life was pulled out from under me when I became a mother and, feeling the loss and seeing no escape from it, I tried acquiescing. I tried to let go, to be “only” a mother. I sunk into depression and loneliness. Then I quit drinking and reshaped my career. Building my life more intentionally around teaching and writing fulfilled me—woke me up somehow. It allowed me to feel human again.

Perhaps what we mean by “ambition” is a woman’s simple desire to feel human? A woman’s right to participate in public life? To leave the home at all?

I guess I have “ambitions outside the home.” But my “ambitions” are to be in conversation with others, to be in community, to write and make things, to have freedom of movement and mind, to not be alone and depressed and addicted to things. My goals are both lofty and not.

A mother’s desire to work outside the home, in other words, is not always tied to careerist egoism, which is the undertone I hear in “ambition.” Sometimes, the desires that emerge from the trauma of American motherhood are much greater— which is to say much smaller. We find we want to be a person, have a mind, have a right to our body, connect with a community, care for—or just be in—the world.

What I’m circling around here is a recurrent stumbling block for feminist politics: this inability to move beyond the binary thinking that structures how we talk about mothers and work, and being a mother or not. Choice feminism situated us in agency and autonomy, important human rights. Women, we said, should be able to choose whether they want to mother or work. They should be able to choose between being a SAHM or WORKING MOM.

As if these are the only choices! As if we could not be more inventive!

I have written before about how the current childcare crisis and the work crisis are linked. Just as motherhood will not fulfill us, neither will work. But for some, that is, like, a truly terrifying, eye-roll-inducing statement. Then what will fulfill us, Amanda?

Idk. But I am not saying that nothing in life is fulfilling, even if, in our present cultural moment, many people feel that way. I am saying that the “choice” women are usually offered relies on the supposition that a life is made of either “choosing between” or “balancing” career aspirations and family life. That’s it, there’s nothing else here for us. Just those two poles of identity, forever competing, the end.

In her essay, “The Grand Shattering,” Sarah Manguso writes:

For years, I asked writers who were also mothers how they prioritized the various components of their identities — was Writer below Mother, and if so, would it be possible to reverse that? One woman told me that her identity wasn’t a ladder but a pie chart containing slices of variable sizes. That answer sounded to me like an oblique admission that she wasn’t a writer first. Since I didn’t want to be anything but a writer first, I dismissed her.

Claudia Dey writes in an essay:

Here is the artist-mother’s bar graph: line one—the multiplying size and need of her expression—held up against line two—the rapid dissolution of time.

I love these ladders, pie charts, bar graphs. These experiments with mapping the self feel much truer than simplistic statements about women being free to Work, as though that would in and of itself offer liberation.

Later in “The Grand Shattering,” Manguso writes about a change of heart that occurred after she became a mother:

[Women] are given few reasons to value motherhood and many reasons to value individual fulfillment. They are taught, as I was, to value self-realization as the essential component of success, the index of one’s contribution to the world, the test of our basic humanity. Service to the world was understood as a heroic act achieved by a powerful ego. Until I’d burrowed out from under those beliefs, being a writer seemed a worthier goal than being a mother.

Part of my process for fulfilling my own “ambitions” over the past few years has been to turn more forcefully toward writing and the world of ideas because I had previously turned so far away. This has meant participating in a host of professional activities that make me feel sick and twisted up inside, especially those that occur on the internet. It has meant hawking myself as a good / trying not to get wrapped up in hawking myself as a good.

Some of this has been awful and awkward and uncomfortable and depressing. Some of it has been beautiful and wonderful and a reminder that I like people and teaching and talking and making things with others.

The problem I have found is: I think I do have “ambition,” and the sinister kind. I grew up in Los Angeles. How could I not?

But there’s more to it than that. I worry about money, as I have since I was young. In “Notes on Work”, Weike Wang describes how growing up with a scarcity mentality changed the way she thinks about work:

“my family’s lack of [money] was so often the cause of distress and conflict when I was younger that I could never become one of those people for whom money doesn’t exist.”

Wang also writes about the masochistic quality of the hustling creative:

“When I get to the end of a particularly overloaded day, my voice hoarse from teaching, my mind buzzing from far too many e-mails, questions, and deadlines, I vow never to let that happen again, knowing full well that, as soon as I’ve achieved a new level of exhaustion, my id will push me to try to exceed it.”

We have no healthy concept of work outside hustle culture. Good work is work that is voluminous and done. Good workers are busy workers. They aren’t those engaged in deep or careful or creative work. Good workers are showy workers. Bosses. Stars. $$. We always feel as though we’re falling behind, or that we’re almost there.

I have been off social media for about three days, trying to reset, if not my ambitions, then the way my brain functions. My goal is to stay off social media until the end of the shortest month of the year. But it feels like I am not doing my job! What am I missing? Who is missing me? All funny because I do not get paid to be on social media and only rarely get paid to write.

Trying to be “authentically” oneself on the internet so that one can fulfill their ambitions to write (or do anything that requires an audience) is a gamble. Or in #boss parlance, an “investment.” The stakes are high if your income is rooted in your writing or teaching or editing or other precarious side hustle.

My sense is that most people are tired of hearing other people complain about being on the internet. Most people are also tired of hearing mothers complain about working or not working. All this exhaustion, though, seems to route us back to the problem. We are all tired. We all must perform so many forms of work for free so that we can do the work that pays us not enough, so stop whining, we say, which is a nice way to sidestep the urgency of structural change, which is also exhausting to think about.

And so it has become standard for writers to receive all sorts of advice about being on the internet. Brand yourself! Know your audience!

Kimberly Harrington wrote about the writer’s many forms of work in her newsletter recently—about how the ancillary work of being a creative or intellectual or online person can become all-consuming. The essay is a great read, and you should go experience the whole thing, but I was particularly struck by her observations about how our constant being-online-ness changes what we expect from what we read.

Harrington cites Brandon Taylor, who writes:

[…] has digital life gotten to the point where everything is an argument to be won? Is every piece of writing trying to exert an influence upon you? When I sit down to write, I am not always trying to convince people of things.

In writing, as in life, I am a fixer. When some aspect of the world is troubling me, which is often, I turn to my critical impulses. My creative brain shuts down. I move into analysis mode. If I can just binge-think this problem, my brain says, everything will be okay!

Without much googling, I can deduce this is some kind of trauma response (my therapist confirms). My impulse to put on my analysis hat when things feel tough is also a result of how I grew up, in a family that struggled because of everyone’s desire to be “right,” rather than just be or feel or listen. It’s a result of being a trained academic—of the idea that knowledge production should be divorced from the embodied self making their way through the world.

I do not put much stock in the idea that criticality always exists in opposition to radical world-building (i.e. the logic of phrases like: “it’s harder to build something new than tear things down,” as if every meaningful movement in history has not required both criticality and imagination, holding hands). But I am trying to move away from this tic that Taylor captures so well. This demand that writing Always Be Thesis-ing. Which seems to be related to the demand that writers Always Be Branding Themselves.

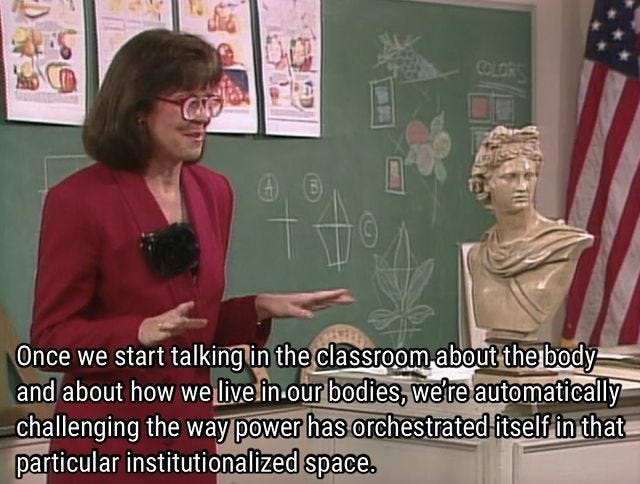

Writing, like teaching, is an inherently revolutionary form of work. Teaching is healing work, as bell hooks said. I think writing is, or can be, too. But just as educational institutions have been tainted by power, so has the world in which writing moves. Creativity, though, is always there, writing as a practice is always there, for the taking. It has an element of labor to it, but at its core writing is closer to spirituality, to care, than it is to Work.

I have come to believe that there is a difference between turning toward Work as we understand it, which is failing all of us—and which I equate with individualistic “ambition”—and turning toward community, care, creativity, change. Maybe this is just a way for me to excuse my own “ambitions.” I’m open to that critique. But I don’t think it’s only that.

Just as there is no conscious consumption under capitalism, there is no conscious form of work. Everything is implicated, though, undoubtedly, some forms of work are more implicated in exploitation and individualism and other evils than others.

For some this leads to a throwing up of the hands. What are we supposed to do? Idk. We’re all doing our best. You’re doing great. But the question makes me think of something else Manguso wrote, in conversation, several years ago:

The ambition to write smaller is anti-capitalist and therefore impossible to reconcile with the rules of the marketplace, where, like a hopeful idiot, I continue to bring my small and constrained work to be validated. I also continue to feel the frisson of shameful desire to be glorified, nonetheless, as the marketplace’s great big grand next thing. Yet there’s an icy solace in not being glorified, and a useful freedom, too.

And so I slink, back to my self-imposed, icy detachment from the internet, which for the moment feels just a little liberating.

And here is where I do the thing.

I have some classes coming up!! I would love to read and write and think with you:

@Hugo House: “Labors of Love,” on writing while reading Silvia Federici, Wednesdays, April 13-May 4, 5–7pmPST

Read about the class here; registration opens March 8 for Hugo House members and March 15 for non-members

@Corporeal Writing: “Writing And/As The Mother,” starts April 22, asynchronous reading and writing, with optional Zooms on Fridays 12pm-1pmPST, April 22-May 20

Email me if you have any questions: amandaemontei@gmail.com

I'm so looking forward to your class on writing and Silvia Federici!

Amanda, I love that we both were noodling on Ambition this week but from different perspectives. It is worth unpacking what we mean by ambition which, you are right, can mean different things to different people. This line, I loved: Perhaps what we mean by “ambition” is a woman’s simple desire to feel human? A woman’s right to participate in public life? To leave the home at all?

Yes, I think that is what I am touching on, not that I become a CEO or earn a 6 figure income, but my daring desire to put my voice out into the world, whether through writing, or in community, or in conversation with others. Also, your phrase: "the trauma of American motherhood." Holy shit. Can we have a whole post about that please? I can offer my own case study!

And I agree that right now, we have so little in between career life and home life. Could some of this be a component of the pandemic? What happened to valuing community service, fun, travel, volunteering except the opportunities disappeared during the last two years and we've forgotten what it was like to have more than work/home life?

Also that Brandon Taylor quote. And thanks for sharing the Sarah Manguso essay. Reading it now!