This is the third essay in a series on low libido and the medicalization of desire. You can read the first essay on the myth of libido here, and the second essay, which includes women’s firsthand accounts of their libidos, here. To support this work, upgrade your subscription.

Sexual freedom is under attack. The kinds of sex people should be having, who they should be having it with, in what relationship contexts, and to what end, are all central to the platform of religious extremists, tech-bros, pronatalists, and the like.

It’s almost laughable to think that, given how frankly these groups are talking about their desire to control and narrowly define gender, sex and reproduction, we are still talking about libido as though it’s a gas tank that for women mysteriously begins to run on empty at the age when they wake up to the inequality that is baked into the world in which they live, or in the years during which they find themselves struggling to live up to the expectations of contemporary parenthood and heterosexual marriage.

Any decent medical professional who meets a patient complaining about low libido should begin by asking what exactly they mean by such a term— to uncover what might be going on under the surface. Dr. Lauren Streicher, for instance, who is a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, says her first goal with such patients is to suss out whether there is any pain or physical discomfort at play. Medical conditions like cardiovascular or thyroid disease, childbirth, and the side effects of prescription medications can affect a person’s sexual enjoyment, and therefore influence the likelihood a person will want certain kinds of sex. Physical complications are often treatable, such as by changing medications, or by prescribing something to increase lubrication or lessen discomfort.

Physical changes — whether caused by age, disease or differing abilities — can of course also be treated simply by exploring other ways to have sex. But medical professionals tend to look for medical solutions; it’s in the job description.

When people reference their libido, however, they are usually referencing some interplay between body and mind, between arousal and desire. And when a person is struggling because they no longer think about or want sex as often as they once did — that is, when they struggle more broadly with their own sexual desire — the list of possible reasons is extraordinarily long.

“It’s very rarely a quick fix,” Streicher says. “You can’t ignore the psychosocial stuff, past experience and trauma, and the cultural stuff, and the religious stuff.”

She uses a 50-question intake form to help identify her patients’ sexual history. The screener also includes questions ranging from the physiological to the emotional, because to even begin to understand a person’s thoughts and feelings about sex, we have to consider mental health, relationship satisfaction, cultural and religious beliefs, and lifestyle, including the kind of economically-induced work stress most people are under today.

I asked numerous sex therapists, sex researchers, and doctors how it’s possible, then, for any medical professional to be sure they are dealing with what is still often termed, in medical fields, “sexual dysfunction” or a “desire disorder,” when people complain of low libido. They all agreed that, well, they can’t really.

While diagnosis for today’s so-called desire disorders require that a patient self-identify as experiencing either personal or relationship distress as a result of their low desire, identifying why someone might be distressed about their sex life or the frequency with which they want to have sex a certain way or with a certain person, or why they are experiencing distress within a relationship, is much more difficult than identifying that any such distress exists.

For women who carry both the stress of paid and unpaid work, domestic inequality is often a factor. Women, especially if they are mothers, are often working overtime for families and in careers, leaving little time for themselves. Nan Wise, a psychotherapist and sex therapist, has found that most of her patients who are mothers are “depleted” and that “the overfunctioning of caretaking” is one of the biggest stressors in their lives. These women may not even be clinically depressed, but that doesn’t mean they have any energy left for sex at the end of the day.

As I have written before, sex can also become obligatory and rote in many monogamous heterosexual marriages, a hangover over of the origins of marriage, in which sex was quite explictly a wifely duty, all adding to its chore-like quality. When this is accompanied by pervasive inequality in the household, this can seriously complicate a woman’s relationship to consent.

Most women also lack a sense of safety around sexual experiences, whether because they are recovering from past trauma, or because they associate sex with performance. This obviously can impact not only desire and interest in sex, but also the path to arousal. Sex therapists, therefore, often work to assure patients who worry they have low libido that what they are feeling is not a sign of some personal failing, unlike the content of low libido easily found online, which tends to want to convince women there is something wrong with them, in order to sell some service or good. Instead, they work on identifying what’s blocking pleasure, by looking more holistically at a patient’s life.

Just letting go of the idea that one is sexually broken can help relax people and invite more curiosity about what might be blocking pleasure in their lives. But in everyday medical settings, the high level of attention offered by sex therapists and sexual health experts like Streicher is just not occurring. Sex therapists who have studied the long and winding history of desire and sexuality understand that libido is a term that requires meticulous unpacking, and that it is likely to mean many different things to different people, but doctors are not trained to parse out what’s going on with patients who come in worried about their “low libido.”

It’s no wonder, then, that so many women seek out whatever solutions they can. But the internet is of course filled with misinformation about women’s bodies, further worsened by a long tradition within the field of mental health of hystericizing women and pathologizing sexualities that do not fit the heterosexual status quo. (“Ego-dystonic-homosexuality” was not removed from the DSM until the late-80s, let’s remember.)

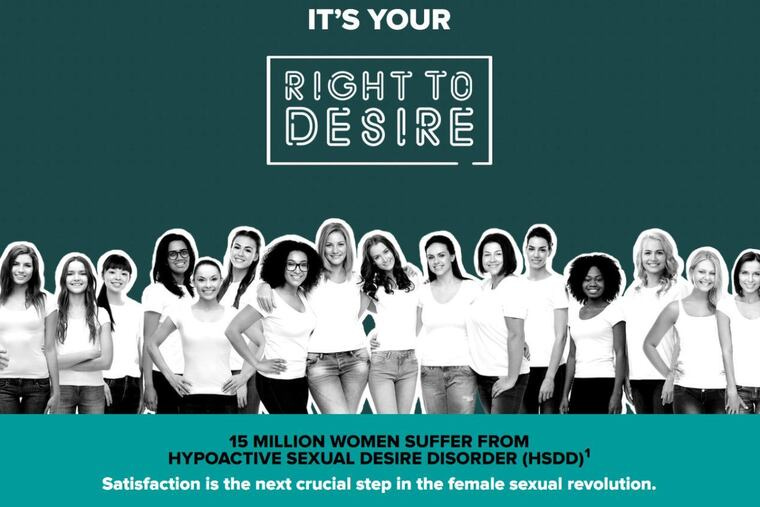

Low libido is not a medical diagnosis— but there are a number of these so-called “desire disorders” that are loosely associated with low libido in medical settings and in popular science writing. And there are sex drugs created by pharmaceutical companies to treat them. Despite heated protests by feminists at their initial FDA approval hearings, these drugs have used marketing campaigns to target women with framing that claims their products are the next step in the sexual revolution, and a form of empowerment for women.

“Hypoactive [low] Sexual Desire Disorder” or HSDD, for instance, is one diagnosis still associated with the notion of low libido. HSDD was first added to the DSM in 1987, and was then defined as a persistent or recurrent lack of interest in or desire for sex. There are two FDA-approved treatments for HSDD in the US— a pink pill and a self-injectable, and both treat the brain, whereas drugs for men, like Viagra, treat blood flow.

If you can’t get the shot covered by insurance (it’s only approved for premenopausal women, weirdly), it’ll cost you $1-2k out of pocket for four shots. The pink pill can cost close to $1k without coverage, per month, and is generally not covered by insurance.

I’m told the drugs have struggled to sell and do not work very well.

Even so, there remains a push to pathologize women’s lack of desire. HSDD was recently merged with “female sexual arousal disorder” (FSAD), defined by a lack of physical response to arousal. One study cites, rather curiously, “a lack of vaginal estrogen, arterial insufficiency, tactile insensitivity, or relationship conflict” as causes for FSAD [emphasis mine!]. One of these things is not like the other.

The new combined diagnosis, termed Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder (FSIAD), is supposed to reflect how closely the mind and body work together in sex— but many feminist sex researchers claim that, in fact, this new diagnosis just makes it easier to pathologize women with any sexual distress, and to treat them with brain-altering drugs. In merging the two previous diagnoses, the waters of women’s sexual health have also been clinically muddied, rather than clarified in any meaningful sense.

We can clearly see this messy analysis of women’s desire reflected in the fuzzy thinking about libido on the internet and in consumer culture today.

Today, sex coaches have swooped into the digital landscape to fill the wide gap caused by a medical industry that medicates but does not seek to understand women’s bodies, and by the failures of a broad lack of sexual education. As with all coaching industries, there are issues with certification and regulation, though many of these coaches do have qualifications that doctors and therapists tend to lack. But these services are so expensive and privatized as to be boutique and inaccessible to most.

The question of whether desire should not be considered a medical issue at all also remains. Desire is forged within a complex web of influences. And desire can be rational— informed by years of sexual experiences or trauma—or entirely irrational, a curious mix of one’s adherence to cultural norms and a conscious or unconscious fidelity to unexplainable fetishes. Usually, it’s a mix, or at best, an active negotiation with the forces that shape our sexual lives and relationships— a form of play.

Untangling more obvious physical issues related to arousal from our thoughts and feelings about sex can go a long way in correcting our cultural misunderstandings of libido. But it’s also not possible to totally control the way the mind and body interact.

Desire, after all, is not only based on sensation, emotion, culture, and the social desires we all experience in our yearnings for what others appear to be having, or to do what others appear to be doing. What we want is also political, a direct engagement with how power shows up within and outside our bedrooms today, and bedrooms past, and more simply, it’s a broad engagement with the world in which we live.

Desire, then, is not something one can or should try to master, treat, cure, or fix. We would do better to think of desire as a creative force continually reshaping itself, both under our control and, in other ways, out of our hands. Which means our own desires will always be a little elusive. It can be part of the fun, if we let it.

And while our current overemphasis on libido distracts from more urgent questions about what we really want and how to get it, the notion of desire at least suggests people can make different choices based on what they are feeling.

Stirring more desire in one’s life requires creating the conditions for pleasure, which means looking at one’s life in a comprehensive way and finding a wider lust for life. That may feel impossible to come by in such a bleak political and cultural moment. Some of the changes needed in one’s life to access that kind of desire again or for the first time may also feel more complex and difficult than we’d like. The lure of the quick fix, however false, might feel less frightening.

Leaving a bad marriage or a relationship with bad sex; confronting the inequality in our own homes and the oppression carried out by those who claim to love us; confronting our own attachment to the standards of beauty and aging and fatphobia and busyness and distraction and disempowerment; asking whether we feel safe enough to open up with partners and stop performing in the bedroom— these responses to disappeared desire are not nearly as easy as overnighting those Lovin’ Libido gummies.

But they are far more promising. And not only for individuals, but for our collective health.