De-Pathologizing Plath: An Interview with Heather Clark

"I often wonder if she would have died by suicide if she’d had a good live-in nanny during the winter of 1963."

I came to Sylvia Plath’s poetry late in my writing and academic life. As an undergraduate, I had a worn-out copy of The Bell Jar, but I started reading Plath more seriously in grad school, when I was pregnant and doing research for my PhD dissertation. In my doctoral program at the time, there was a hard and heated line between confessional poetry and conceptual poetry: the latter understood as a cool critique of power and representation; the former as dated and uninformed about the spectacles of language and subjectivity. As I’ve written in this newsletter before, women’s confessional impulses have often been trivialized.

Part of why I turned to Plath was to contest this characterization of confessional writing. But I also returned to her poetry repeatedly because I wanted some clue about what was on the horizon for me as a mother. Pregnant and reading Plath, I couldn’t help but notice in her poetry an antagonism between motherhood and literary life. This tested me, a soon-to-be mother, a writer who wasn’t writing. I didn’t want to believe that writing and motherhood were fundamentally incompatible – that trying to do both always led to great tragedy. But I could see, even then, that everything we take to be true about creative production (i.e. the conditions in which we expect to write, what good writing looks like) relies on the presence of a woman, just out of frame, taking care of kids and home.

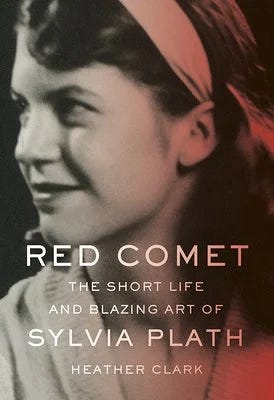

When I read Plath now, six years into motherhood, I cannot help but think about her life. I see a woman trying, impossibly, to fit both ideals: the vision of the unburdened creative, the picture of the doting mother and wife. At that intersection of both longings, she created some of her best writing – poetry filled with rage and a keen sense of male power. In her biography Red Comet: The Short and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath, Dr. Heather Clark writes that Plath’s legacy, nevertheless, has become one of a mad woman, tortured by her own mind. Clark’s incredibly detailed and compelling biography, however, presses against this dominant narrative of Plath as pathology, repositioning her, as Clark writes, as “one of the most important American writers of the twentieth century.”

I corresponded with Clark about female monsters, the competing drives of creativity and maternity, Plath’s experiences with male harassment and motherhood, and whether childcare might have changed Plath's fate. The conversation feels so very timely. Clark’s groundbreaking and score-settling biography was a Pulitzer Prize finalist and was recently named one of the top 5 nonfiction books by the New York Times.