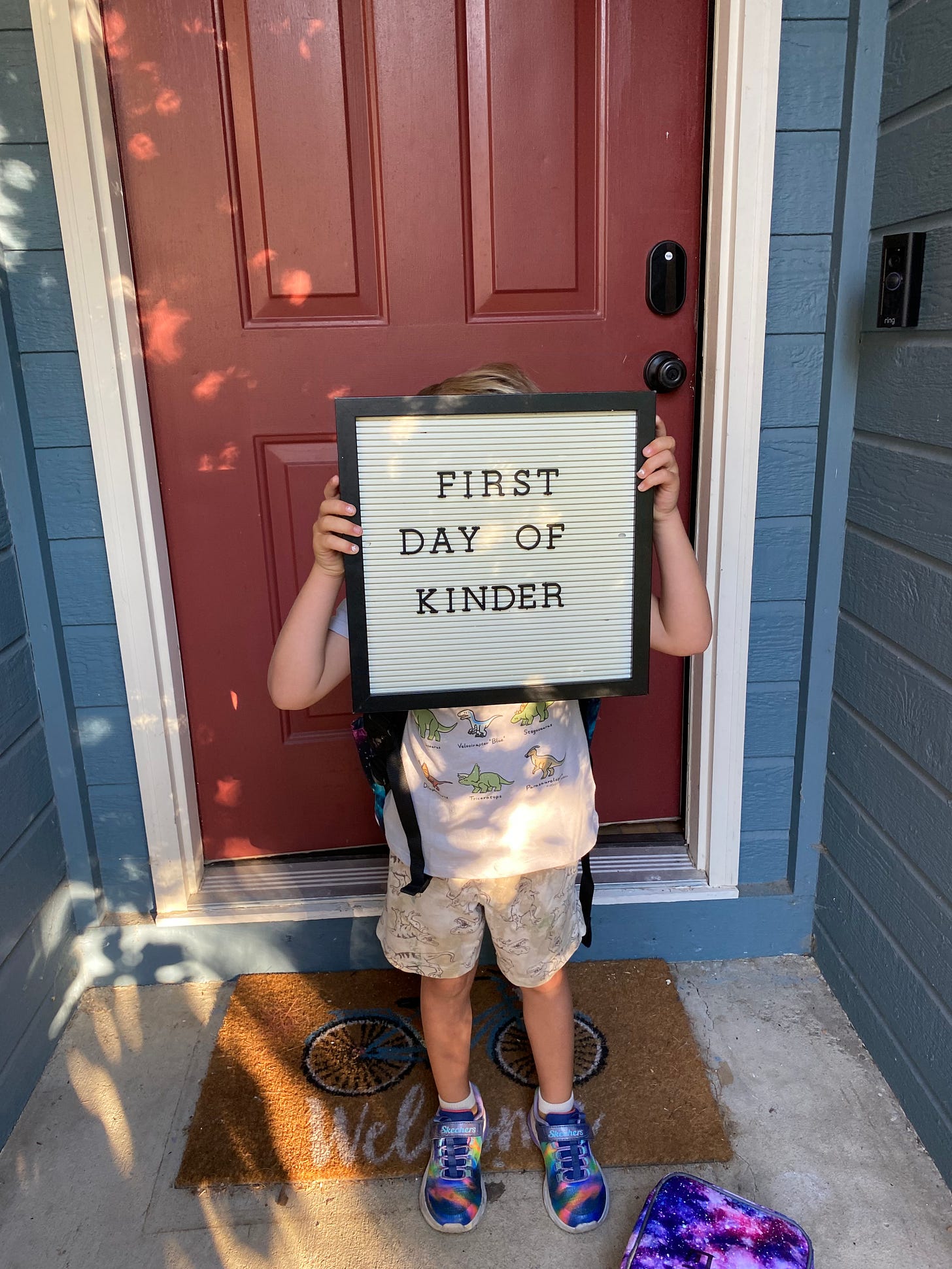

Yesterday my two kids went back to school. My youngest is entering kindergarten and my oldest is now in third grade. Earlier this week, I got a call letting me know the kids had both been accepted to a competitive choice school. If you’re not familiar with the model, these choice schools (we have a lot of them in the Bay Area) are public schools that take kids from throughout a district based on a lottery system.

Our local choice schools are pretty diverse and most are high performing, but we declined the invitation to move schools and chose to stay instead at our lower performing, dual-language immersion magnet— an under-performing school that was transformed a few years ago into an elementary + middle that focuses on bilingual immersion and has a multi-cultural emphasis. This is the second time we’ve declined.

There have been many aspects of my kids’ current school that have worried me— too much time spent on Chromebooks, lots of teacher absences, a new middle school that has no real shape or plan yet. I’d like to say the choice was easy. If I’m being honest with myself, however, much of my worries come from the white parental tendency to want what’s best for my kid, and not think too far beyond that. But we’ve also stayed because I have been trying to fight that urge, think bigger, and I know there are other metrics by which to measure education beyond test scores.

I’ve been doing some interviews for Touched Out and one issue that keeps coming up, which I hope will continue coming up, is the question of choice, and how we understand it as a concept. As I have said and will continue to say, we need a more nuanced way to talk about the idea of choice and agency. Many people tend to think choice is something one has or does not have, and they get very uncomfortable when anyone says otherwise.

In America, we have lived for a long time with a rhetoric of free will, but in truth, the ability to choose the circumstances of one’s life— how you will parent, where your kids will go to school, how safe you and your children will be, whether to have children or not—is influenced by systems of power. When we talk about school “choice,” this detail is often missing from the conversation. What parents have the ability to choose where their children go to school, to agonize over the options as I did, or to choose whether their children will feel safe there?

It is not so much that some of us have choices and others do not, but that a variety of factors influence the degree to which we can choose the paths our lives, and our children’s lives, will take.

In an era in which the term “parental rights” is used to argue for control and censorship, as well as the right to do nothing about gun violence, the subject of public education is just one realm in which the issue of “choice” is weaponized against those arguing for better public policy. You have a choice, they say. You can just homeschool your kid if you don’t like the reality of a failing public education system!

But choices are complicated and actually not always that simple. They are continually limited and ushered around by public policy, cultural expectations and social coercion, emotional and professional and economic limitations, themselves influenced by dynamics of gender, race, class, sexuality, and the history that some don’t want taught in schools.

One sleight of hand that conservative Americans have performed in recent years is to propose that banning books, censoring curriculum, and a denial of this history is a campaign for “choice,” and therefore greater freedom. But “parents’ rights” simply means endowing a small minority group of parents with the ability to rob other children and families of their own agency, autonomy, and choice. No one should have that right.

Further reading: